Monday, November 28, 2022

Public interest theory.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

Top-secret internal communication by DERG regarding the population of Welkait and Tsegede

Top-secret internal communication by DERG regarding the population of Welkait and Tsegede

Top-secret internal communication by DERG regarding the population of Welkait and Tsegede (Western Tigray, Ethiopia), 1984 (Version 1) [Archive].

Source and context: Zenodo

Summary: During the civil war in Ethiopia between the military “Derg” regime and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) the Dejena mountain range in Welkait became, around 1980, the main base for Tigray resistance against the Derg regime that was in power at the time.

In the Ethiopian federal state, after 1991, Welkait became part of Tigray, Western Tigray zone, which is contested by the core Ethiopian Amhara elites.

A rare communication document between Derg’s military command and the Ministry of Defense, dating back to 1984 has been retrieved, where they lament that the population of the Welkait and the adjacent Tselemti districts supports the TPLF, because the people are Tigrinya speakers.

Up to now, the archive is top-secret, and photos of the document were furtively taken.

This typical document from the 1980s, prepared on carbon copy paper using a ge’ez font type writing machine, was shown to a well-informed Ethiopian analyst, who confirmed its authenticity.

Derg regime on Welkait

A top-secret correspondence among DERG administrators in 1984 complaining that TPLF was freely moving in Welkait and Tsegede, because the people are Tigrinya speakers

https://www.quora.com/What-region-of-Ethiopia-does-the-area-called-Western-Tigray-rightfully-belong

TRANSLATION

Very urgent

Top secret

From: Transitional Military Government, North Western Command First command

To: Ministry of Defense, Addis Ababa

Date: 04/16/1984

The first sentence reads as follows:

“1.2. People

Because the TPLF has been freely roaming in Welkait and Tsegede weredas for the last five years and the people are Tigrinya speakers, the TPLF has found it easy to put them under pressure with its propaganda.”

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

A well informed analysis of the Pretoria and Nairobi deals to end the Tigray war

A well informed analysis of the Pretoria and Nairobi deals to end the Tigray war

To keep the fledgling peace process on track, the AU and Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a Horn of Africa regional body, need to continue coordinating efforts with African governments and other outside actors like the U.S., UN and European Union (EU). Collectively, they should urge Tigray’s leaders and the federal government to uphold their commitments in the peace deals, working first to ensure Eritrean troops’ withdrawal, lest Tigray use their continued presence as a reason to delay disarmament.

INTERNATIONAL CRISIS GROUP

Source: International Crisis Group 23 NOVEMBER 2022

On 2 November, Ethiopia’s federal government and leaders of the country’s northern Tigray region agreed to end two years of devastating war. The welcome deal, brokered by the African Union (AU) in the South African capital Pretoria, was a triumph for Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, as Tigray’s embattled leaders assented to disarm their forces and restore federal authority in the region. In exchange, the Ethiopian military, and Eritrean troops who had been fighting alongside federal forces, halted their advance toward Tigray’s capital, Mekelle, and Addis Ababa said it would end its de facto siege of the region. In follow-up talks, Tigray authorities secured an additional pledge that Eritrean forces would withdraw. Fighting between the two sides has stopped. Yet the fragile calm could shatter, especially with thorny questions outstanding and Tigrayans already backtracking on commitments. Both sides need to honour their pledges while keeping up momentum in talks. External actors must seize this moment to coax the parties toward consolidating peace and insist on immediate unrestricted aid to Tigray.

The conflict, among the world’s deadliest, erupted in Africa’s second-most populous country in late 2020, as Ethiopia struggled to navigate a complex political transition. Abiy rose to power in 2018, after three years of protests partly against the rule of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which had dominated Ethiopia for almost three decades, creating a repressive system that brought development gains but bred discontent. The TPLF believe that Abiy’s government sidelined them, cutting them out of a rapprochement with their former comrade and then archenemy, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, and singling out Tigrayans for prosecution for corruption and human rights offences. For their part, Abiy’s allies argue that the TPLF never accepted losing power, blocked reforms and sought to sabotage the new authorities. As the power struggle simmered, Mekelle’s leaders proceeded in 2020 with regional elections in Tigray, in defiance of federal authorities, who had postponed the vote due to COVID-19. The constitutional crisis escalated when the federal and Tigray governments cast each other as illegitimate.

On 3 November 2020, saying they feared an imminent federal military intervention, Tigray’s forces attacked the national army command in the region.

The standoff soon boiled over. On 3 November 2020, saying they feared an imminent federal military intervention, Tigray’s forces attacked the national army command in the region (some Tigrayan federal officers sided with the regional forces). Addis Ababa promptly launched an offensive in Tigray, blocking all roads into the region, starving it of food and other supplies and cutting off telecommunications, electricity and banking services – an approach that left almost all of Tigray’s roughly six million people in desperate need of humanitarian assistance. In the war’s first few months, the neighbouring Amhara region took control of Western Tigray, which it claims as historical Amhara territory, in a campaign that rights groups described as ethnic cleansing. Eritrea also joined the battle on the federal side, with Isaias seemingly hoping to deal his old foe, the TPLF, a decisive blow.

Momentum seesawed over the course of the war. At the outset, Ethiopia’s military, backed by Eritrean troops and foreign drones, captured Mekelle and forced the TPLF into the mountains, only to hastily retreat as Tigray insurgents (motivated in part by atrocities committed by Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers against civilians) retook the regional capital in June. Citing the continuing blockade, Tigray’s forces marched southward to Addis Ababa, occupying towns and committing their own atrocities along the way. With supply lines stretched, they withdrew to Tigray in December 2021, after a federal counteroffensive gained pace, with mass mobilisation and drones purchased from Turkey playing key roles. An uneasy lull in fighting then settled in. In March, the federal government declared a unilateral humanitarian truce, speeding up delivery of food and medicine to Tigray. The TPLF also held its fire. But efforts to start formal peace talks foundered, partly because Mekelle said Addis Ababa must first end its blockade by restoring services to the region and allowing trade.

The war tipped decisively in the federal government’s favour after the truce broke down on 24 August, and full-scale conflict re-erupted. Ethiopia rapidly assembled a large number of troops to attack Tigray on several fronts, moving in with Eritrean forces from the north west and leading an offensive with Amhara allies from the south. By all accounts, there were huge casualties in spectacularly bloody infantry warfare, with sources close to both sides estimating that more than 100,000 died on the battlefield in a two-month span. Though Tigray’s fighters stood their ground at first, the allied forces broke through their lines in October in key locations, capturing the northern cities of Shire (a strategic crossroads), Aksum and Adwa, as well as the southern towns of Alamata and Korem. On the back foot militarily, Tigray’s leaders then called for another truce, lowering their conditions to unfettered aid access and Eritrean forces’ withdrawal, leading the AU to convene the two parties in Pretoria.

Tigray’s negotiators went to South Africa desperate for a pause in fighting, and reaching that goal came at a high price. Indeed, the deal’s terms reflect the heavy military pressure Tigray’s forces were under in the face of Eritrean artillery and superior federal logistics, manpower and firepower, including in the air. In the deal, the TPLF committed to laying down arms within 30 days and allowing federal forces to re-enter Mekelle in order to restore constitutional order and take control of federal institutions. The deal also stipulates that, once Ethiopia’s parliament has lifted its May 2021 designation of the TPLF as a terrorist organisation, the TPLF and the federal government are to appoint an “inclusive” interim administration to govern Tigray until elections. This provision represents a significant concession, as it implies that Tigray’s September 2020 regional polls, which the TPLF won in a landslide and which helped spark the civil war, lacked legitimacy. For its part, the federal government agreed to halt its offensive upon Mekelle, while also promising to restore services to Tigray, as well as allow unfettered aid deliveries.

Tigray’s leaders appear to have eventually realised that ending the conflict is the best way to ease the Tigray population’s suffering.

None of the parties has come out of the war with credit. For Tigray’s negotiators, the extent of concessions offered to secure a truce illustrates the scope of the predicament they found themselves in, besieged on all sides by determined adversaries, including two national armies. While both sides share blame for starting the conflict, the TPLF miscalculated – at a cost of countless lives – first by escalating its feud with Abiy after losing power, next by underestimating its opponents and plunging into war, and then by erecting obstructions to peace talks during the autumn lull in fighting. Tigray’s leaders appear to have eventually realised that ending the conflict is the best way to ease the Tigray population’s suffering. As for Addis Ababa, it has rightly attracted international opprobrium for its methods, including what UN investigators found to be the use of starvation as a tool of war against Tigray’s civilians. In the end, though, Abiy’s government also chose peace, opting to halt an offensive that appeared to be on the brink of forcing the TPLF from power again and instead advance federal objectives through talks.

The parties showed early commitment to the Pretoria pact, a positive sign. Most importantly, the two battle-exhausted sides have stopped fighting, although unconfirmed reports continue to filter through of serious abuses in and around Axum and Shire by Eritrean and Amhara forces. Addis and Mekelle also followed through on a commitment for top military commanders to meet within five days to negotiate how to put the Pretoria accord’s security provisions into effect, producing a follow-up agreement on 12 November in Nairobi.

That subsequent deal maintained critical momentum but also created more uncertainty and diluted disarmament plans. Instead of the ambitious, perhaps even unrealistic, original 30-day timeline, the Nairobi deal gave Mekelle more breathing space, splitting disarmament into two phases and, crucially, tying it to foreign and other non-federal forces’ withdrawal. For the Tigrayans, the pull out of Eritrean troops – the foreign forces the deal refers to, even if not explicitly – is a core demand that was less clearly addressed in Pretoria (that deal said, for example, the parties would cease “collusion with an external force hostile” to the other). The military commanders agreed Tigray would give up “heavy weapons” (presumably tanks and artillery) as non-federal forces withdraw from the region, while punting the timeline for relinquishing small arms to talks due to conclude on 26 November. The parties also agreed to disengage their front-line forces in four distinct zones by 23 November (thus far this appears incomplete), after which Addis Ababa is to restore basic services to the region, while assuming its federal “responsibilities”.

The Nairobi agreement, however, included no precise terms as to how or when Tigray’s leaders would meet their commitment to facilitate the federal military’s re-entry into Mekelle, suggesting that they also won some reprieve from honouring that pledge. Tigray leaders now insist privately that this step might entail a limited security escort for returning federal officials, which would be a far cry from the triumphal procession that the Pretoria accord seemed to envision. With no progress made so far at re-establishing the federal presence in Tigray’s capital, this issue requires further negotiation.

It is far from clear that Tigray is planning to hand over all its arms even if Addis Ababa meets its obligations.

For all the positive developments, the situation thus remains fragile, demanding extreme vigilance from all actors. There are signs that Tigray’s leaders are wavering on the Pretoria accord’s critical terms. Hesitation on their part would, perhaps, not be surprising, given the deal’s lopsided nature, but it would nonetheless be alarming. It is far from clear that Tigray is planning to hand over all its arms even if Addis Ababa meets its obligations. Further, in a 13 November statement, issued the day after the Nairobi agreement, Tigray’s leaders publicly backtracked on parts of the Pretoria deal, including by explicitly rejecting its effective removal of the existing regional government from power. It is unclear if they are posturing to deflect internal criticism of their initial concessions in Pretoria or to position themselves for future negotiations. But regardless, the statement suggests willingness to renege on a key part of the accord, namely that Tigray’s authorities would step aside for an interim administration negotiated between the TPLF and the federal government.

Despite the odd unhelpful comment from his allies, Prime Minister Abiy has publicly welcomed the deal and stressed that more war would be futile. Such remarks are welcome, as sustained provocations from both sides otherwise risk undermining the frail accord by emboldening hardliners, perpetuating the deep mistrust and making a return to war more likely. For example, should the federal government move slowly on lifting all aspects of the blockade (perhaps in response to Mekelle’s backtracking on some of Pretoria’s terms), Tigray’s leaders could stall on disarmament, especially if the Eritrean army or Amhara forces linger in Tigray. That, in turn, would lead Addis Ababa to refuse to fully reconnect and reopen Tigray, creating conditions in which any spark might ignite yet another round of disastrous large-scale hostilities.

A further concern is that the two sides do not yet appear to share compatible visions for how a settlement will emerge, making clear how delicate the process will be. Tigray’s leaders want Abiy to pivot away from his alliance with Isaias. Yet it seems safer to assume that Addis Ababa will want to avoid ruffling the feathers of either the Eritrean leader or Amhara allies. Both Abiy and Isaias could well choose, at least for now, to keep their forces ready for renewed hostilities, thereby keeping Tigray’s authorities boxed in militarily. Further, Tigray’s leaders hope that, eventually, the federal government will allow much of their military force to join the federal army or re-hat as regional security forces. Whether Abiy will pursue integration is a matter of conjecture, however. Some think he could do so to help rebuild the Ethiopian military, while others suggest he will prefer to keep Tigray forces that have just tried to oust him out of the national army. Continuing to make incremental progress, at the negotiating table but also with tangible measures on the ground, will thus be key to preventing the rickety process from falling apart.

Abiy faces an especially thorny balancing act with regard to Eritrea, a key partner in the war that may be satisfied only by Tigray’s almost complete disarmament. Indeed, it will be difficult if not impossible for Abiy to accommodate both Asmara’s insistence that the TPLF be defanged and, on the other hand, Tigray’s security demands. It remains unclear if Eritrea will fully disengage its forces or withdraw, even if Abiy asks it to do so. Should Abiy move to let the TPLF continue as a dominant force in Mekelle, allow Tigray to retain a strong regional force, or integrate large numbers of Tigray’s perhaps 200,000 fighters into the federal military, Eritrea could react defiantly. More than two decades after the last Ethiopian-Eritrean war, new hostilities remain possible if Abiy and Isaias fall out, an additional factor showcasing just how complex the peace process could prove.

Abiy will also need to tread carefully in relations with Amhara political leaders, his other major ally in the war – and an important domestic constituency. The Nairobi accord appears to require Amhara regional forces and militias (the other “non-federal forces” it cites), which have been fighting alongside the Ethiopian army, to also withdraw from Tigray. Yet Amhara regional authorities will be keen not to lose out in the peace process. The complicating factor is Tigray’s loss of territory to Amhara during the war, as Amhara forces captured Western and Southern Tigray, which many Amhara refer to as Welkait and Raya, respectively, in asserting historical claims to the territories. Addis Ababa and Mekelle are unlikely to see eye to eye on the withdrawal of Amhara forces from what the Pretoria agreement called “contested areas” (without specifying which areas these are), a major dispute that could gum up disarmament negotiations.

Ideally, over time, Tigray and Amhara leaders would recognise the need to resolve their differences through dialogue.

What is clear is that the process for addressing these competing territorial claims will need to be central to further political dialogue, as envisaged in Pretoria. One approach could be for the federal government to assert control over the areas, paving the way for the return of displaced people and political processes to adjudicate the disputes. Such a move would infuriate Amhara leaders and activists while failing to placate Mekelle, which would doubtless argue that returning to the constitutional order means restoring Tigray’s pre-war borders. Still, an initial assertion of federal control, if that can be done peacefully, may be the most pragmatic option for the time being. Ideally, over time, Tigray and Amhara leaders would recognise the need to resolve their differences through dialogue, including through provisions for administering the areas that navigate the competing claims and complex local identities.

Should the peace agreement hold, the parties will also need to negotiate on the make-up of Tigray’s administration. Addis Ababa is in a strong position to dictate the political terms in Tigray, but that would be risky given the region’s historical attachment to autonomy, which long predates the federal era. To foster stability, federal leaders should strive to ensure that Tigray’s rights to self-rule under the constitution (which offers considerable regional autonomy, even legalising secession) are respected as constitutional order is restored.Thus, Addis Ababa should avoid imposing an interim administration that is likely to breed continued resistance. For its part, the TPLF needs to accept that a new regional government will be formed in line with the Pretoria deal, which will mean dilution of its authority. Some Tigray nationalist opposition parties that will demand a governing role have offered stinging criticism of the TPLF’s Pretoria concessions and aspire to independence, a sign of how difficult it will be to create a balance within the interim government and reintegrate Tigray into Ethiopia after such a divisive war.

To keep the fledgling peace process on track, the AU and Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a Horn of Africa regional body, need to continue coordinating efforts with African governments and other outside actors like the U.S., UN and European Union (EU). Collectively, they should urge Tigray’s leaders and the federal government to uphold their commitments in the peace deals, working first to ensure Eritrean troops’ withdrawal, lest Tigray use their continued presence as a reason to delay disarmament. Should verified withdrawals start to occur, they must then stress to Tigray’s leaders the need to begin handing over their tanks and artillery. While remaining clear-eyed about the challenges, the U.S., UN and EU envoys and other partners should constantly remind their Ethiopian interlocutors that they have chosen the path of peace, as there is no route to outright military victory. A return to war would have terrible consequences for civilians and corrode Ethiopia’s stability for years to come.

The AU and regional officials have an especially vital role to play in trying to ensure that the truce does not break down. The AU’s high representative, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, and co-mediators former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and former South African Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, as well as key IGAD officials, especially its Executive Secretary Workneh Gebeyehu (a former Ethiopian foreign minister) and Special Envoy Mohamed Ali Guyo (a veteran Kenyan diplomat), now face a tall order. They will need to keep the parties progressing toward fulfilling their promises, while also ensuring that talks, including about a detailed disarmament plan, maintain forward momentum. Given especially the lack of trust between the parties, an AU team of experts should immediately start monitoring the truce, as agreed in the Pretoria deal. Foreign governments should provide as much support as possible to what on paper looks like a severely under-resourced monitoring mission.

All international actors should push in unison for immediate unrestricted humanitarian access to Tigray.

All international actors should push in unison for immediate unrestricted humanitarian access to Tigray, even as initial indications give reason for modest optimism. To further hold the parties accountable, donors, the UN and NGOs should be transparent about whether or not the federal government and its regional allies are still choking humanitarian access, and insist also on services being comprehensively restored. They should also speak out if Tigray’s authorities divert humanitarian supplies to their forces, as occurred just prior to the last round of fighting, when Mekelle seized World Food Programme tankers, saying the agency had not returned fuel Tigray had loaned it.

The U.S., EU and other outside actors also need to carefully weigh how to keep encouraging progress through their actions. To make the dividends of peace more concrete, the U.S. and EU should pledge donor conferences to help rebuild a peaceful Tigray as well as adjacent parts of Afar and Amhara affected by the war. They should take care to balance the need to continue protecting the budding process with the urgency of providing assistance to Ethiopia’s suffering economy. In particular, they should resume substantial non-humanitarian financial support to Addis Ababa only after the peace process has made clear, tangible progress. That means waiting until Eritrean forces withdraw behind the internationally recognised border, the federal government restores services to Tigray, aid flows freely and political talks with Mekelle get under way.

Despite the difficulties of roping Eritrea into a constructive peace process, the AU and other African intermediaries should reach out to Asmara to urge it to withdraw from Tigray, support the Pretoria and Nairobi agreements, and pursue any of its demands through dialogue. It is also high time Ethiopia settled its long-running border disputes with Eritrea, which helped spark the catastrophic 1998-2000 war between the two countries and remain central to Asmara’s narrative of grievance. Addis Ababa should reiterate its intention to implement in full the 2002 UN border commission ruling, which identified some key disputed areas as Eritrean. Ideally, even if they appear to be in no position to object at the moment, Tigray’s leaders would play their part in this decision, as their exclusion was a key defect of Abiy and Isaias’ 2018 rapprochement that promised a definitive resolution of the border dispute.

Cementing peace will require courageous political leadership from both Abiy and his Tigrayan counterparts. In particular, Abiy should continue speaking about the benefits of peace and act generously toward his erstwhile foes. Mekelle, meanwhile, should recognise the futility of a renewed armed insurgency, and the extreme peril it holds, both for the TPLF’s own future and for Tigray’s population. That message should also be heeded by Tigrayans who criticise the Pretoria agreement, including both those living in Tigray itself and those in the diaspora, with the latter acknowledging that Tigray’s leaders made painful political concessions in part due to their sober assessment of the fighting’s human toll and their battlefield prospects. In sum, all parties should remain patient. They should focus on making incremental progress that will gradually build the trust needed to find an eventual settlement.

The halt in hostilities and agreement to end the war could help Ethiopia and Ethiopians turn a page on this tragic chapter, provided they are a first step on a long road to recovery. The brutal two-year conflict inflicted vast human suffering. Tigray’s immiseration bears witness to its leadership’s miscalculations, even as the conflict has set a frightening precedent with the tactics employed by Addis Ababa and Asmara against their adversaries. Mekelle should now stick to its responsible decision to stop fighting, while Abiy, choosing magnanimity over vindictiveness, should be pragmatic about the region’s disarmament and gradually seek a sustainable settlement with Tigray that can begin to heal the conflict’s deep wounds. All parties should put their efforts into giving peace the chance it deserves.

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

November 20, 2022. ‹‹የእኛ ብሔርተኝነት የበሰለና ዴሞክራሲያዊ ነው›› አቶ በቴ ኡርጌሳ፣ የኦነግ የፖለቲካ ኦፊሰርቆይታ Reporter :by Yonas Amare.

ከባህር ዳር ዩኒቨርሲቲ በባዮሎጂ፣ ከወለጋ ዩኒቨርሲቲ በኢኮኖሚክስ፣ ከአርሲ ዩኒቨርሲቲ ደግሞ ማስተርስ ኦፍ ቢዝነስ አድሚኒስትሬሽን፣ እንዲሁም ከኒው ጄኔሬሽን ዩኒቨርሲቲ በሄልዝ ኦፊሰርነት ተመርቀዋል፡፡ ገና ባህር ዳር ዩኒቨርሲቲ ሳሉ በኦሮሞ ተማሪዎች ማኅበር ውስጥ ይንቀሳቀሱ እንደነበር የሚናገሩት አቶ በቴ ኡርጌሳ ሥርዓቱ የፖለቲካ ጥያቄ የሚያነሱ ሰዎችን የማይታገስ ስለነበር በጊዜው እስራት እንደገጠማቸው ይናገራሉ፡፡ ይህ ሁኔታ በዩኒቨርሲቲ ከሚንቀሳቀሱ የኦሮሞ ነፃነት ግንባር (ኦነግ) ተማሪዎች ጋር የበለጠ እንዲቀራረቡ፣ ከዚያም ወደ ፖለቲካ ትግል ለመግባት እንዲወስኑ እንዳደረጋቸው ይናገራሉ፡፡ በአሁኑ ወቅት የኦነግ የፖለቲካ ኦፊሰር የሆኑት አቶ በቴ ድርጅታቸው በሰላማዊ መንገድ ለመንቀሳቀስ ከስደት ቢመለስም፣ ነገር ግን በሚደርስበት ከፍተኛ ጫና መደበኛ ሥራውን ለመሥራት መቸገሩን ይናገራሉ፡፡ ፓርቲያቸው ኦነግ ሌሎች ሕዝቦችን በጠላትነት የማይፈርጅ፣ የጠራና የበሰለ የፖለቲካ መስመር እንደሚከተል የሚናገሩት አቶ በቴ፣ ከፓርቲያቸው ጉዳይ ባሻገር በቅርብ ጊዜ እየተባባሰ ስለመጣው የኦሮሚያ ቀውስና ስለኦሮሞ የፖለቲካ ትግል ከዮናስ አማረ ጋር ያደረጉት ቆይታ እንደሚከተለው ቀርቧል፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- የኦሮሞ የፖለቲካ ጥያቄ ምንድነው?

አቶ በቴ፡- ኦሮሞ ጥያቄ ሳይሆን የፖለቲካ ፍላጎት ነው ያለው፡፡ ጥያቄ ከሆነ የሚመልስ አካል አለ ማለት ነው፡፡ ኦሮሞ ግን ማግኘት የሚፈልጋቸው የፖለቲካ ፍላጎቶች ናቸው ያሉት፡፡ የአቢሲኒያ ኢምፓየር ሲስፋፋ ኦሮሞና የሌሎች ሕዝቦች ፖለቲካዊ ፍላጎት በኃይል ተደፍጥጦ ቆይቷል፡፡ የአቢሲኒያ ኢምፓየር መስፋፋት አፋኝና ጨፍጫፊ ስለነበር፣ በተለያዩ የኦሮሚያ ክፍሎች ተቃውሞና ትግል ይካሄድ ነበር፡፡ የሜጫና ቱለማ እንቅስቃሴም ሆነ የኦነግ እንደ ድርጅት መመሥረት የዚያ ሒደት ውጤት ነው፡፡ የኦሮሞን የፖለቲካ ፍላጎት ወይም ጥያቄ ሕዝቡ ያነሳው እንጂ ኦነግ አልፈጠረውም፡፡ ኦነግ ጥያቄውን ተመርኩዞ፣ የፖለቲካ ፕሮግራም ቀርፆና ተደራጅቶ አታግሏል፡፡ ኦነግ የተለያዩ የኦሮሞ ብሔርተኞችን በአንድ የፖለቲካ ርዕዮተ ዓለም ወይም መስመር እንዲታገሉ በማድረግ የመጀመሪያው ድርጅት ነው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ሌሎች የፖለቲካ ድርጅቶች አልነበሩም ወይ? በርካታ የኦሮሞ ወጣቶች እንደ መኢሶን (የመላው ኢትዮጵያ ሶሻሊስታዊ ንቅቃቄ) ባሉ የፖለቲካ ድርጅቶች ውስጥ ገብተው ሲታገሉ አልነበረም ወይ?

አቶ በቴ፡- ኦሮሞዎችማ በብዙ የፖለቲካ አሠላለፎች ውስጥ ነበሩ፡፡ አፋኝ ብዬ ባስቀመጥኩት ሥርዓት ውስጥም እኮ ኦሮሞዎች ነበሩ፡፡ ኦሮሞዎች ከምኒልክ ጋርም ነበሩ፡፡ እነ ሀብተ ጊዮርጊስ ዲነግዴና ባልቻ አባ ነፍሶም የምኒልክ አንጋሾች ነበሩ፡፡ ነገር ግን እነርሱም ቢሆኑ በአቢሲኒያ ኢምፓየር መስፋፋት ሰለባ የሆኑና የተማረኩ ነበሩ፡፡ ሥርዓቱን ተቀብለውና በዚያ ውስጥ አድገው ለሥርዓቱ ሲያገለግሉ የኖሩ ናቸው፡፡የኦሮሞ ሰው በዚህም በዚያም ውስጥ አለና ያ ሥርዓት የኦሮሞ ማኅበረሰብን ይወክላል የሚሉ ሰዎች ተሳስተዋል፡፡ በኢትዮጵያ ፖለቲካ ታሪክ ኦሮሞ ሁለት ሚና ነበረው፣ ገዥም ተገዥም ነበር ብለው የሚከራከሩ ወገኖች አሉ፣ እኛ ይህንን እንቃወማለን፡፡ አንድን የፖለቲካ ሥርዓት ያንተ የሚያደርገው መሠረታዊ የሆኑ የአንድን ኅብረተሰብ እሴቶችን ሲወክል ነው፡፡ የግለሰብ በአንድ የፖለቲካ ማኅበር መግባት፣ ማንነቱን አጥቶና ገብሮ ለሥርዓቱ መታገሉ አይደለም ያን ሥርዓት ያንተ የሚያደርገው፡፡ ያ ሥርዓት በአንተ ውቅር፣ ማንነትና ባህል የተቀረፀ በመሆኑ ነው አንተን የሚወክል ሥርዓት ነው የሚባለው፡፡

የአቢሲኒያ ሥርዓት በአፄ ኃይለ ሥላሴ ጊዜ ነው ለመጀመሪያ ጊዜ የኢትዮጵያ መንግሥት የተባለው፡፡ ይህ ሥርዓት ደግሞ በዋናነት መገለጫዎቹ በዋናነት ኦማርኛ ተናጋሪነት፣ የኦርቶዶክስ ሃይማኖትን የመንግሥት እምነት አድርጎ የያዘ፣ በዘር ወይም በደም ሥልጣን የሚወራረስ ሥርወ መንግሥት ነው፡፡ አማርኛ ተናጋሪ ሲባል ሥርዓቱ የአማራ ነው ለማለት አይደለም፡፡ በሥርዓቱ ውስጥ አማራ ስለመኖሩ እኛ አናውቅም፡፡ እንዲህ ያደረገው የአማራ ብሔረሰብ ነው ብለን ጠቅሰን አናውቅም፡፡ ሥርዓቱም የአማራ ነው አላልንም፡፡ ነገር ግን ሥርዓቱ ሌሎች የቋንቋ ቤተሰቦችን የጨቆነና እንዲቀሩ ያደረገና በዋነኛነት አማርኛ መናገርን ያስቀደመ ነው፡፡ ኦርቶዶክስ ቤተ ክርስቲያን የመንግሥት ሃይማኖትና አንጋሽ ነበረች፡፡ ንጉሦችን የምትቀባ፣ በጦርነትም ታቦት ይዛ የምትዘምት እንደነበረች ይታወቃል፡፡ የአቢሲኒያ ኢምፓየር ሥሪቱ ይህ ሲሆን በባህሪው ተስፋፊ፣ ጠቅላይና ቅኝ ገዥያዊ ሥርዓት ነው፡፡ የአፍሪካ ቀንድን የአውሮፓ ኮሎኒያሊስቶች ሲቀራመቱት እርሱም የራሱን ድርሻ ቆርሶ በመውሰድ የተፈጠረ ነው፡፡ ምኒልክ ያደረጉት ልክ ፈረንሣዮች፣ እንግሊዞችና ጣሊያኖች በአካባቢው ሲያደርጉት እንደነበረው ነው፡፡

የኃይለ ሥላሴ መንግሥት በብሔር ብሔረሰቦች ትግል በዋናነት ሲገረሰስ አገሪቱ ሥሪቷ ሳይፈርስ በአንድነት መቀጠል ነው የሚያስፈልጋት ያሉ ሶሻሊስታዊ ኃይሎች አገር መምራት ጀመሩ፡፡ ፊውዳላዊው ሥርዓት ከተገረሰሰ ጭቆና በአገሪቱ አይኖርምና ሁሉም ማኅበረሰብ እኩል የሆነበት ኢትዮጵያን መፍጠር እንችላለን በሚል ሶሻሊስታዊ ርዕይ ነበር አገሪቱን የመሩት፡፡ እኛ ይህ የኦሮሞን ጥያቄ የማይመልስ ነው ብለን ተቃውመን ስንታገለው ቆይተናል፡፡ ኦነግ ለመጀመሪያ ጊዜ የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ቋንቋው፣ ባህሉና ማንነቱ የተከበረበት የራሱ አገር ይኑረው ብሎ ፍላጎቱን ግልጽ አድርጓል፣ ለዚህም ሲታገል ነው የኖረው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ኦሮሞ በኢትዮጵያ ማዕቀፍ ውስጥ የራሱን ማንነት፣ ባህልም ሆነ ቋንቋ ማሳደግ ይችላል የሚሉ በርካቶች አሉ፡፡ ከሌሎች ሕዝቦች ጋር በፈጠራት ኢትዮጵያ ፍላጎቱን አስከብሮ መኖር ይችላል ብለው የሚያምኑ የፖለቲካ ኃይሎች አሉ፡፡

አቶ በቴ፡- ብዙ ጊዜ ኦሮሞ ያልሆኑ ወገኖች መለየት ያቃታቸው ጉዳይ እሱን ነው፡፡ አንዳንዴ ጉዳዩን ኦነጋዊያን ብለው የሚመድቡት አሉ፡፡ የኦሮሞ ጥያቄ ምንድነው ብለው የሚያነሱት አሉ፡፡ ይህ ግን ሊገባቸው ስለማይፈልጉ ወይም እያወቁ ስለሚያድበሰብሱ የሚነሳ ጥያቄ ነው፡፡ ኦሮሞ ትልቅ ማኅበረሰብ ነው፡፡ በኦሮሞ ውስጥ ብዙ አመለካከቶች ቢኖሩ የሚደንቅ አይደለም፡፡ ቅኝ ገዥው ሥርዓት እስካሁንም የዘለቀ በመሆኑ የነበረው ጭቆና፣ የባህል ጫናና የማንነት ማሳነስ ብዙ ሰዎችን የተለያየ አመለካከት እንዲይዙ የሚያደርግ ነው፡፡ እኛ የምናነሳውን የኦሮሞ ጥያቄ የሚቃወሙ ኦሮሞዎች የሉም ብለን አናምንም፡፡ በኦሮሞ ውስጥ ሦስት ዓይነት የፖለቲካ ዝንባሌዎች አሉ፡፡ አንዱ ነባሩን አሀዳዊ ሥርዓት ማስቀጠል የሚፈልግ ነው፡፡ በምኒሊክም ሆነ በኃይለ ሥላሴ ዘመን ሥርዓቱን ያገለገሉ ነበሩ፡፡ በሥርዓቱ ውስጥ ቁንጮ የነበሩና ኃይለ ሥላሴም ጭምር በደም ኦሮሞ የሆኑ በርካታ ናቸው፡፡ በደርግም ቢሆን ኢትዮጵያ ወይም ሞት ብለው በኤርትራና ትግራይ ተራሮች የተሰውና ይህችን ኢምፓየር ለማስቀጠል ብዙ ዋጋ የከፈሉ የኦሮሞ ልጆች ነበሩ፡፡

በሌላ በኩል ፌዴራላዊት ኢትዮጵያን እንደግፋለን የሚሉ ኃይሎችም አሉ፡፡ በኢትዮጵያ ግንባታ ሁሉንም ዓይነት ሚና ነበረን፣ በታሪክ አጋጣሚ ተዋህደናል ተዋልደናል፣ ብዙ አገሮችም የሚፈጠሩት በዚህ መንገድ ነው የሚሉት እነዚህ ኃይሎች የራሳችንን ዕድል በራሳችን የመወሰን መብት ሳንነጠቅ በፌዴራላዊ ሥርዓት ከሌሎች ሕዝቦች ጋር መኖር ይሻላል የሚሉ ናቸው፡፡ በራሳችን ክልል ራሳችንን እያስተዳደርን ከሌላው ኢትዮጵያዊ ጋር በሰላምና በጋራ መኖር ለኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ይበቃዋል የሚሉ ናቸው፡፡ የራስን ዕድል በራስ መወሰን ከኢትዮጵያ ማዕቀፍ መውጣት ሳይሆን፣ በኢትዮጵያ ውስጥ ከመገንጠል ውጪ ራስን በራስ እያስተዳደሩ መኖር ነው የሚሉ አሉ፡፡ እኛ የነፃነት ኃይሎች ግን በታሪክ አጋጣሚ በእንዲህ ዓይነት የፖለቲካ ሥርዓት ውስጥ ብንጠቃለልም ወደ ነበረን የቀደመ የብሔር ክብር መመለስ እንችላለን ብለን እናምናለን፣ አለብንም፡፡ ነፃ አገር ለመሆን የሚያግደን ነገር የለም፡፡ በኢኮኖሚ፣ በፖለቲካ፣ በሚሊታሪም ሆነ በጂኦግራፊ ትልቅ ሕዝብ ስለሆንን ራሳችልን ችለን መቆም እንችላለን፡፡ ነገር ግን የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ፍላጎቱ ከሆነ ከሌሎች የኢትዮጵያ ሕዝቦች ጋር የመኖር መብቱ ሊከበር ይገባል፡፡ ይህ በቂው ነው ብለን መወሰን ግን ተገቢ ነው ብለን አናምንም፡፡

የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ እስከ ዛሬም የራሱን ዕድል በራሱ የመወሰን ዕድል አላገኘም፡፡ ይህ ዕድል ተሰጥቶት በፈቃዱ ከመረጠና በኢትዮጵያ ውስጥ መኖር እፈልጋለሁ ካለ መብቱ ነው፡፡ አልያም እኛ እንደምንለው ነፃ መንግሥት እፈልጋለሁ ካለ አገር የመመሥረት መብቱ ሊከበርለት ይገባል እንላለን፡፡ እኛ ይበቃዋል ብለን የምንገድበው አይደለም፡፡ አንደኛ ኦሮሞ ብሔር ነው፣ ብሔር ደግሞ አገር መሆን ይችላል፡፡ ሁለተኛም ኦሮሞ በግድ ነው የተጠቃለለው፡፡ በግድ ሥርዓት የተጫነበት ሕዝብ ደግሞ ራሱን መግለጥ መቻል አለበት፡፡ ድርጅታችን ወደ አገር ቤት ሲመለስም በሕጋዊ መንገድ ኦሮሞ አገር የመሆን መብቱን መጎናፀፍ ይችላል ብሎ በማመን ነው፡፡ በኢትዮጵያ ሕገ መንግሥት በአንቀጽ 39 በግልጽ እንደተቀመጠው ኦሮሞ ለዘመናት የታገለለትን ያን መብቱን በሕግ ማዕቀፍ ማግኘት ይችላል ብለን ነው የምንታገለው፡፡ ኢሕአዴግ በሕግ ቢያስቀምጥም በአሠራር ግን ያስቀመጠውን የሚቃረን አሀዳዊ በመሆኑ ያንን ዓይነት የውሸት ፌዴራላዊ ሥርዓት ተቃውመናል፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ደርግ በወደቀ ማግሥት በነበረው የሽግግር ሒደት ስድስት የኦሮሞ የፖለቲካ ድርጅቶች ተሳትፈዋል፡፡ ኦነግ በወቅቱ ከሕወሓትም ሆነ ከሻዕቢያ ያልተናነሰ የመሣሪያም የፖለቲካም አቅም ነበረው፡፡ አሁን ያለው ሕገ መንግሥት እኮ የሕወሓትና የኦነግ የፖለቲካ ዶሴ ነው ተብሎ ይተቻል፡፡ ሕገ መንግሥቱንም ሆነ ፌዴራላዊ ሥርዓቱ የሚቃወሙ ኃይሎች በሽግግሩ ሒደት አልተወከልንም ይላሉ፡፡ በዚያ ወቅት በብዙ የፖለቲካ ኃይሎች የተወከለው ኦሮሞ በፌዴራላዊ ሥርዓቱ ለመቀጠል አልመረጠም ሲባል ከዚህ ጋር አይጋጭም ወይ? ሥርዓቱ የተገነባበትን ነባራዊ ሀቅ መካድ አይደለም ወይ?

አቶ በቴ፡- በጣም ጥሩ ጥያቄ ነው የተነሳው፣ ሆኖም ታሪክን መካድ አይደለም፡፡ ለዚህ መልስ የታሪክ ነጠብጣቦችን በትክክል ማገናኘት አስፈላጊ ነው፡፡ የሽግግሩ ቻርተር የኦነግ አመራሮች በግልጽ የተሳተፉበት ነው፡፡ ሰናፌ ላይ ቅርፁን የያዘው የድርጅቱ ምክትል ሊቀመንበር ሌንጮ ለታ ትልቅ አስተዋጽኦ ያደረጉት ቻርተር ነው፡፡ በዚያም ከለንደን ኮንፈረንስ በኋላ በነበረው ሻዕቢያና ሕወሓት ያልካቸው ኃይሎች የነበሩበት ስምምነት ውስጥም ኦነግ ነበረበት፡፡ የኃይል መመጣጠን ነበር የሚባለው ግን የተጋነነ ነው፡፡ የፖለቲካና የኃይል አሠላለፍ በአብዛኛው ለብዙዎች ይምታታል፡፡ በፖለቲካ ኃይል ከሆነ ኦነግ በጊዜው ከሕወሓትም በላይ ገዝፎ ነበር፡፡ በሌሎች ማኅበረሰቦች ጭምር ትልቅ ተቀባይነት አግኝቶ ነበር፡፡ አቶ ገላሳ ዴልቦ ጎንደር ሄደው ያደረጉት ንግግር ታሪካዊ ነው፡፡ ወልዲያ ላይ ኦነግ ቢሮ ከፍቶ ነበር፡፡ አዲስ አበባም ሆነ ሌሎች አካባቢዎች ሰፊ የማኅበረሰቡን ድጋፍ አግኝቶ ነበር፡፡ ከምርጫ በፊት በነበረው ቅድመ ምርጫ (ስናፕ ኢሌክሽን) ኦነግ በአዲስ አበባ 70 በመቶ አሸንፎ ነበር፡፡

ይህ ሁሉ የፖለቲካ የበላይነት የነበረው ኦነግ ግን በጊዜው ከሕወሓት ወይ ከሻዕቢያ የሚሊታሪ የበላይነት ነበረው ማለት አይቻልም፡፡ ሕወሓት፣ ብአዴን፣ ኦሕዴድና ደኢሕዴግ ተብሎ በመቀላቀል ኢሕአዴግ በአደረጃጀት የፈጠረው ኃይል ቀላል አልነበረም፡፡ ወደ ሽግግሩ ሲገባ ሕወሓት 150 ሺሕ፣ እንዲሁም ሻዕቢያ 200 ሺሕ ሠራዊት የነበራቸው ሲሆን ኦነግ ግን 20 ሺሕ ጦር ነው የነበረው፡፡ በፖለቲካው ኦነግ ተቀባይነትና የበላይነት ቢኖረውም ነገር ግን በሚሊታሪው አለመመጣጠን ነበር፡፡ ከቅድመ ምርጫው (ስናፕ ኢሌክሽን) በኋላ ግን በኢሕአዴጎች ዘንድ ከፍተኛ መደናገጥ በመፈጠሩ ከፍተኛ ርብርብ በኦነግ ላይ ተጀመረ፡፡ በብዙ የኦሮሚያ አካባቢዎች የሕወሓትና የኢሕአዴግ ጦር ሰፍሮ ነበር፡፡ የኦነግን መዋቅርና ካድሬ ማደን ተጀመረ፡፡ ኦነግ የነበረው በቻርተሩ ጊዜ ነበር፡፡ ሕገ መንግሥቱ ረቆ ሕገ መንግሥታዊ ሥርዓት እስኪጀመር ማለትም ከ1984-87 ዓ.ም. ባለው ጊዜ የሽግግር መንግሥቱን የሚመራ መንግሥት ለመመሥረት ምርጫ ይደረግ ሲባል፣ ኦነግ የሁላችንም ታጣቂ መሣሪያውን አስቀምጦ ለተሃድሶ ወደ ወታደራዊ ካምፕ ይግባ የሚል ጥያቄ አቀረበ፡፡ ይህን ደግሞ ኢሕአዴግም ሻዕቢያም ደገፉ፡፡ የሦስትዮሽ ኮሚቴ በአሜሪካ መንግሥት ተዋቅሮ ሠራዊታቸው ወደ ካምፕ እንዲገቡ ተደረገ፡፡ ኦነግ የፖለቲካ የበላይነት ስለነበረውና በምርጫ እንደሚያሸንፍም በመተማመን ነበር ሙሉ ሠራዊቱን ወደ ካምፕ ያስገባው፡፡ ይሁን እንጂ ኢሕአዴግ ወደ ካምፕ የተወሰነውን ልኮ በቀረው ኃይል የኦነግን ሠራዊት ማሳደድ ጀመረ፡፡ ማምለጥ የቻሉት የኦነግ አመራሮች ወደ ጫካ ገቡ፡፡ ኦነግም በዚያ መልክ ከቻርተሩ ተገፍቶ ወጣ፡፡ ምርጫ ላይ አልደረሰም፣ ሳይሳተፍ ነው የተገፋው፡፡ በቻርተሩ ጊዜ ግን ኦነግ 12 ወንበሮች ነበሩት፡፡ እንዲያውም በአንዳንድ አጋጣሚዎች የደቡብና የሌሎች አካባቢ ተወካዮችን ከጎኑ በማሠለፍ የድምፅ የበላይነት ሁሉ ያስመዘግብ ነበር፡፡ ኦነግ 52 የቻርተሩ ተወካዮችን ድምፅ በማስመዝገብ ኢሕአዴግን አሸንፎ ያስወሰነበት ጊዜ ሁሉ ነበር፡፡ ይህ የፖለቲካ ቅቡልነቱ ነው ለኦነግ ጠላት የፈጠረለት፡፡ ኦነግ የተገፋው ደግሞ በሰኔ የሽግግር መንግሥት ምርጫ ሊካሄድ ቀጠሮ በተያዘበት ሰሞን ነበር፡፡

በወቅቱ የተስማሙት የራስን ዕድል በራስ የመወሰን መብት በሕገ መንግሥቱ መፍትሔ ስለሚበጅለት፣ በሒደት የኦሮሞ ሕዝብም መወሰን ይችላል በሚል ነበር፡፡ ኦነግ በወቅቱ ሻዕቢያ አሸንፌያለሁና የኤርትራን መንግሥት መሥርቻለሁ በሚል የሄደበትን መንገድም ተቃውሞ ነበር፡፡ ይህን ያደረገው ደግሞ የሽግግር ሒደቱ ታልፎ በሕጋዊ መንገድ ውሳኔው ይደረስበታል ከሚል ቀና የፖለቲካ አመለካከት ነበር፡፡ የፖለቲካ ተንኮልን ሳያገናዝብ የኦነግ አመራር በወሰደው ውሳኔ ዋጋ እንዲከፍል ተደረገ፡፡ በሕዝቦች እኩልነት መንፈስ የፌዴራል ሥርዓቱ ቢመሠረት እዚያ ላይ የከረረ ጥላቻ የለንም፡፡ ለዚያ ነበር ኦነግ የተለሳለሰው እንጂ የራስን ዕድል በራስ የመወሰን ጉዳይን ኦነግ ከፕሮግራሙ አላነሳም፡፡ በሽግግር ሒደቱ የተወሰኑ የፖለቲካ ኃይሎች አልተሳተፉም ሲባል እሰማለሁ፡፡ በተለይ የአማራ ድርጅቶች አልነበሩም፣ አማራ አልተወከለም ሲባል እሰማለሁ፡፡ በወቅቱ ግን የአማራ ድርጅቶች አልነበሩም፡፡ የተገፉት እንዲያውም የኢትዮጵያ አንድነትን የሚያቀነቅኑት የመኢሶንና የኢሕአፓ ድርጅቶች ነበሩ፡፡ ብአዴን የአማራ ድርጅት አይደለም የሚለውን ክርክር ወደ ጎን ብዬ ከብአዴን ውጪ የአማራ ድርጅት አልነበረም፡፡ የአማራ ልሂቃን የሚባሉት እነ ፕሮፌሰር መስፍን ወልደ ማርያም ይከራከሩ የነበረው ግን አማራ የሚባል የዘውግ ማንነት የለም ብለው ነበር፡፡ አማራ የሚባል የዘውግ ማለትም በደም የሚተላለፈው የዘር ወይም የብሔር ማንነት የለም ብለው ሲከራከሩ፣ እንዲያውም እነ መለስ ዜናዊ ነበሩ አለ ብለው የተቃወሙት፡፡ አማራ የሚባል የጋራ ቋንቋ፣ ባህልና ሥነ ልቦና ያለው ማኅበረሰብ እስካለ ድረስ አማራ ሊወከል ይገባል ያሉት ኢሕአዴጎች ናቸው፡፡ ያን ግን ፕሮፌሰሩና በጊዜው የነበሩ የአማራ መሪ ልሂቃኑ ከሰውነት ማነስ አድርገው ነበር የቆጠሩት፡፡ ፕሮፌሰር አሥራት ወልደየስ ዩኒቨርሲቲውን ወክለው ነበር በወቅቱ የተካፈሉት እንጂ አማራን አላሉም፡፡ እርሳቸው ንቅናቄ ነበር የመሠረቱት፡፡ ንቅናቄው ግን የፖለቲካ ጥያቄዎች ያነሳ ስለነበር ሲቪክ ማኅበር ሆናችሁ ማንሳት አትችሉም ስለተባሉ ነበር መአሕድ (የመላው አማራ ሕዝብ ድርጅት) ወደ መመሥረት የገቡት፡፡ አብዛኛው የአማራ ምሁር እኛ ከኢትዮጵያዊነት ወርደን በአማራነት አንደራጅም ነበር ያለው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- የአማራ ኃይሎች ብቻ አይደለም እኮ በወቅቱ ሥርዓቱ ሲፈጠር አልተካፈልንም የሚል ጥያቄ የሚያነሱት፡፡ በብሔር ማንነት አንደራጅም ያሉ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነን የሚሉ ወገኖችም ሥርዓቱ ሲፈጠር አልተወከልንም ይላሉ እኮ?

አቶ በቴ፡- እርሱን በግሌ በደንብ እቀበላለሁ፡፡ የታገዱት መኢሶንም ሆነ ኢሕአፓ ኢትዮጵያዊ ኃይሎች ናቸው፡፡ በኢሕአዴግ ውስጥ የነበረው ብአዴን ግን በአማራ ክልል ከቀበሌ ጀምሮ ሕዝቡን ሲያደራጅ ነበር፡፡ አማራን እወክላለሁ ብሎ ክልሉን ሲመራ ነበር፡፡ ሕገ መንግሥቱም ቢሆን በአማርኛ ነው የተጻፈው፡፡ ይህ ሁሉ ታልፎ አማራ አልተወከለም ማለት ለእኔ አይዋጥልኝም፡፡ በሽግግሩ ውስጥ የነበሩ ኦሮሞ ድርጅቶች ሁሉም ተገፍተው ወጥተው ኦሕዴድ ብቻ ነበር የቀረው፡፡ ይህ ሁሉ ሆኖ ግን እኛ በሒደቱ አልተወከልንም አላልንም፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- አማራ መወከል የምፈልገው በኢትዮጵያዊ ኃይሎች ነው ብሎ ከሆነስ? የኢትዮጵያ ኃይሎች መገፋታቸውን ደግሞ ተቀብለውታልና ከዚህ አንፃር አልተወከልኩም የሚለው ከመጣስ?

አቶ በቴ፡- አማራ በኢትዮጵያዊ ኃይሎች ነው መወከል የምፈልገው ብሎ የወጣበትን ጊዜ አይቼ አላውቅም፡፡ እንዲያውም በተቃራኒው ነው ሲሆን የማየው፡፡ ለምንድነው እነ ኢዜማ ከባህር ዳር የተባረሩት?

ሪፖርተር፡- አሁን ያለው የፖለቲካ ስሜት ከ1983 ዓ.ም. ፍፁም የተለየ መሆኑ ይታወቃል እኮ፡፡

አቶ በቴ፡- አዎን የተቀየረ ነው፡፡ ነገር ግን ያን ጊዜም ቢሆን ‹‹ፖፑላር ሰፖርት›› (ሕዝባዊ ድጋፍ) እንጂ፣ በተጨባጭ በኢትዮጵያውያን ኃይሎች ልወክል ብሎ የተሰባሰበ ወገን አልነበረም፡፡ ውክልና መደበኛ በሆነ መንገድ የሚወከለው ወገንን ፈቃድ ማግኘት ይጠይቃል፡፡ የተወካይ ውክልናን በሕጋዊ መንገድ መቀበል ይጠይቃል፡፡ እንዲሁም የምትወክለው ነባራዊ ሀቅ ሊኖር ይገባል፡፡ በፌስቡክ እንደሚታየው አልተወከለም የሚል ዘመቻ ማድረግ ሳይሆን በመደበኛ መንገድ ተደራጅቶ፣ ተፎካክሮ፣ አሳምኖ ውክልናን መያዝ ይጠይቃል፡፡ እውነት ለመናገር አሀዳዊው ኃይል ግን በወቅቱ የተሸነፈ ኃይል ነበር፡፡ ጦርነት ነበር፡፡ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነን የሚሉ ኃይሎችም ተሸንፈው ነበር፡፡ መኢሶንም ሆነ ኢሕአፓ እኮ በጊዜው ከደርግ የተለዩ አልነበሩም፣ ሁሉም አሀዳዊያን ነበሩ፡፡ ኦነግ፣ ሕወሓትና ሻዕቢያን ጨምሮ ለብሔር የታገሉ ናቸው፡፡ ሥልጣን እንጂ አይዲዮሎጂ (ርዕዮተ ዓለም) አይለያያቸውም፡፡ አሸንፎ የመጣው የራሱ ራዕይ ነበረው፡፡ በብሔር መደራጀት ላይ የተመሠረተ ፖለቲካን ይፈልግ ነበር፡፡ ብሔሮች እንዳይጨቆኑ ዋስትና የሚሰጥ የፖለቲካ ሥርዓት ይፈልግ ነበር፡፡ ይህም ቢሆን ግን የተሸነፈውና ተገፋ የተባለው ኢትዮጵያዊ ኃይል እንዲገፋ ኦነግ አይፈልግም ነበር፡፡ መገፋታቸውን ተቃውሟል፡፡ በጊዜው የሕዝብ ድምፅ ይብዛም ይነስም መወከል አለበት ብለን ተቃውመናል፡፡ ደርግም ቢሆን በሽግግሩ ቢካተት ኦነግ ቅሬታ አልነበረውም፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ባለፉት 30 ዓመታት የመገፋፋት ፖለቲካ አልነበረም ወይ የነገሠው? አገሪቱ በመሠረታዊ የአገር መገለጫዎች እንኳ መስማማት ያቃታት በዚህ የተነሳ አይደለም ወይ? በአንድ ባንዲራ፣ በአንድ ብሔራዊ መዝሙርና በሌሎችም የአገር መገለጫ እሴቶች መስማማት የጠፋው በዚህ የመገፋፋት ፖለቲካ አልነበረም ወይ?

አቶ በቴ፡- የኢሕአዴግም ችግር ሥልጣንን በኃይል አግኝቻለሁና በኃይል አስጠብቃለሁ ብሎ ማመኑ ነው፡፡ ደርግን ደምስሻለሁና በኃይል ፍላጎቴን ላስፈጽም የሚል አካሄድ ነው በእኛና በኢሕአዴግ መካከል ፀብ የፈጠረው፡፡ ለመታገል ከእኛ የቀደመ ባይኖርም አራት የሚኒስትርነት ቦታ ጥለን ነው የወጣነው፡፡ የኢሕአዴግን ጠቅላይነት ስንቃወም ነው የኖርነው፡፡ በዚህ እኛ ልንወቀስ አንችልም፡፡ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነኝ የሚለው ኃይል ቢሆን የሌላውን የፖለቲካ ኃይል አመጣጥ መረዳት መቻል አለበት፡፡ በጊዜው የተገፋው ኢትዮጵያዊ የሚባለው ኃይል አልነበረም፡፡ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነኝ የሚለው ኃይል እንዲያውም የተደራጀና በተገቢው የሚመራ ኃይል አልነበረም፡፡ አሁን ሊኖር ይችላል፣ በዚያን ጊዜ ግን ከወደቀው ኢሠፓ በቀር አንድም ኃይል አልነበረም፡፡ ሀቀኛ የፖለቲካ ትግል ያደረጉ ድርጅቶችም ተገፍተው ወጥተዋል፡፡ ኦነግ፣ የሲዳማ አርነት ንቅናቄ፣ ኦብነግ፣ በጃራ አባገዳ የሚመራው፣ የዋቆ ጉቱ ኃይል ተገፍተዋል፡፡ ስለዚህ ኢሕአዴግ በወጣውም ሕገ መንግሥት የሚያምን አልነበረም፡፡ ኢሕአዴግ የፈጠረው ሥርዓት ፌዴራላዊ ይባል እንጂ በገቢር አሀዳዊ ነበር፡፡ ሥርዓቱ ለፌዴራላዊ ኃይሎች ያደላና ኢትዮጵያዊ ኃይሎችን ብቻ የሚገፋ አልነበረም፡፡ ኢትዮጵያዊ የሚባለው ኃይልም ቢሆን ከጥቂት የሚዲያ ጩኸት በዘለለ ብዙዎች የሚደግፉትና የሚሞቱለት የፖለቲካ አሠላለፍ አይመስለኝም፡፡ ትንሽ ሲገለጥ አማራዊ ኃይል ሆኖ ነው የሚገኘው፡፡ መአሕድ የተባለው አማራ ድርጅት በሒደት መኢአድ ተብሎ ነው መታገል የጀመረው፡፡ የኢትዮጵያ ብሔርተኝነት ተብሎ በራሱ የቆመ ሁሉንም አካታች የሆነ የፖለቲካ ዕሳቤ የለም፡፡ አማራና የቀደመው የዘውዳዊ ሥርዓት የሚንፀባረቁበት ነው የሚታየው፡፡ ኢትዮጵያን ወደ ቀደመ ማንነቷና ገናናነቷ እንመልሳለን የሚል ቁመና ነው የሚታየው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ኢትዮጵያን የሠራው ሁሉም ብሔር አይደለም? ከአፄ ምኒልክ ዘመንም አልፈን ብንሄድ ኦሮሞ በጎንደር ቤተ መንግሥት የነገሠበትን ታሪክ፣ የሀዲያ ንግሥት ማዕከላዊ መንግሥቱን የመራችበት፣ የዛጉዌ ሥርወ መንግሥት የተመሠረተበትንና ሌላም ታሪክ አናገኝም ወይ? ኢትዮጵያ ሁሉም ሕዝብ አሻራውን ያሳረፈባት አገር አይደለችም እንዴ?

አቶ በቴ፡- አይደለም፡፡ በአገልጋይነት የገባውን መቁጠር የአንድን ማኅበረሰብ የፖለቲካ ተሳትፎ አያሳይም፡፡ ወደ ኢትዮጵያ ከመጣው የእንግሊዝ ጦር አብዛኛው ህንዳዊ ወታደር ነበር፡፡ ነገርዬው ህንድ ኢትዮጵያን ወረረች አያሰኝም፡፡ የእንግሊዝ ኢምፓየር የህንድ ነበር አያስብልም፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- የኢትዮጵያን ሁኔታ በቅኝ ግዛት መሥፈርት ማስቀመጥ እንዴት ይቻላል?

አቶ በቴ፡- ቅኝ አገዛዝ ነው የምንለው፡፡ የሩሲያ ዓይነት ታሪክ ነው እኮ የእኛም፡፡ የሶቪዬት ኅብረት ቁንጮ የሆነው ስታሊን ጆርጂያዊ ነበር እኮ፡፡ ሶቪዬት ስትፈራርስ ጆርጂያ ነፃ አገር ሆናለች፡፡ ስታሊን ሶቪዬትን ስለመራ ሩሲያ ሆነን መቀጠል አለብን አላሉም፡፡ ኃይለ ሥላሴ በአባት ኦሮሞ ናቸው፡፡ ነገር ግን ንግሥና ስለፈለጉ የእናት ሐረግን ቆጥረው ዘውዱ ይገባኛል ብለዋል፡፡ አማራዊ ሥነ ልቦናን፣ ኦርቶዶክሳዊ እምነትንና አቢሲኒያዊ ሥርዓትን ተቀብለው ነው የኖሩት እንጂ የኦሮሞን ገዳ አልተቀበሉም፡፡ ፊታውራሪ ሀብተ ጊዮርጊስ ዲነግዴ ልጅ ኢያሱ ከሚነግሥ እርስዎ አገር ይምሩ ተብለው ቢጠየቁም፣ እኔ የንጉሥ ዘር አይደለሁም ብለው ውድቅ አድርገዋል፡፡ ይህ የአቢሲኒያዊ ፖለቲካ ተፅዕኖ ነው፡፡ መጽሐፉ ፍትሐ ነገሥትም ቢሆን የሚተርከው ይህንኑ ነው፡፡ ይህን ስንቃወም ነበር፡፡ ከደርግ ውድቀት በኋላም ቢሆን የነበረውን ሥርዓት ኅብረ ብሔራዊ ለማድረግና እሱንም ላለማጣት ነው ኦነግ ሲታገል የኖረው፡፡ ኢሕአዴግን ሕወሓታዊ ሥርዓት ነው ሲባል የነበረው እኮ እነ ኦሕዴድ ቢኖሩም ሁሉንም አድራጊና ፈጣሪው ሕወሓት ስለነበር ነው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- እናንተ ጫካ ገብተናል፣ መስዋዕትነት ከፍለናል ብትሉም እንወክለዋለን ለምትሉት ለኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ከኦሕዴድ የተሻለ ምን አስገኝታችኋል? የኢሕአዴግ ተለጣፊ ስትሉት የቆየው ኦሕዴድ የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ጥያቄዎች እንዲመለሱ ታግሎ ብዙ ድል አስገኝቷል የሚል ክርክር ይነሳል፡፡

አቶ በቴ፡- ትክክል አይደለም፡፡ ለኦሮሞ ብዙ አሳክተናል፡፡ ከኦሕዴድ የተሻለ የሚያደርገን ብዙ ነገርም አለ፡፡ የኦሮሞን ባህል ዳግም እንዲመለስ በማድረግ በኩል ኦነግ ብዙ ሠርቷል፡፡ የኦሮሞን ቋንቋን በማስተማርና በሌሎችም ሥራዎች ኦነግ ከሽግግሩ እስከወጣበት ጊዜ ድረስ በአንድ ዓመት ጊዜ ብዙ ምሥጉን ሥራዎች ሠርቷል፡፡ ኦሕዴዶችን ጭምር ኦነግ ነበር ቁቤ ያስተማረው፡፡ ኦነግ ወሎ የኦሮሞ ነው ብሎ ተከራክሮ ነበር፡፡ አሁን ያለው የኦሮሚያ ካርታ የተሠራውም በኦነግ ትግል ነው፡፡ ኦነግ የታገለባቸው ብዙ ጥያቄዎች ኦነግ ከተገፋ በኋላ ተጨናግፈዋል፡፡ ለምሳሌ ወሎ ወደ ኦሮሞ የመመለሱ ጥያቄ ተጨናግፏል፡፡ ጅግጅጋ የኦሮሚያ ክልል የነበረች ሲሆን፣ ሶማሌ በተውሶ ወስዶ ነው ዋና ክልሉ ከተማ የሆነችው፡፡ ድሬዳዋንም እስከ መካፈል የደረሰው፡፡ አዲስ አበባ የፌዴራል ይሁን ተብላ በማይታወቅ መዋቅር ውስጥ እንድትወድቅ ተደረገ፡፡ ይህ ሁሉ የጨነገፈው በኦሕዴድ ችግር ነው፡፡ ኦሕዴድ አሳካው የሚባለው ነገር ካለ ማሳካት የቻለው በኦነግ ትግል ነው፡፡ የኦነግ ትግል ባይኖር ኦሕዴድ በጠራራ ፀሐይ ተባራሪ ድርጅት ነበር፡፡ በታሪክ አጋጣሚ ለማ መገርሳ ወደ ሥልጣን ከመምጣታቸው በፊት በግል ስናወራ፣ ኦነግ ስላለ ነው እኛ ክብር ያገኘነው ብለው ነግረውኝ ያውቃሉ፡፡ ኦሕዴዶች ክብር ያገኙት በኦነግ ተጋድሎ ነው፡፡ ኦነግ የሚያነሳቸውን ጥያቄዎች ተውሰው ነው በኢሕአዴግ ውስጥ የታገሉት፡፡ ላም ወልዳ ጥጃ ሲሞትባት ወተት መስጠት እንዳታቆም በሚል፣ የሞተችው ጥጃ ቆዳ በጭድ ይሞላና በሕይወት ያለች እንድትመስል አድርጎ ላሟ እንድትልሳት ይደረጋል፡፡ ይህን ስታደርግም ወተት ትሰጣለች፡፡ በኢሕአዴግ ወቅት እነርሱ እዚህ ግባ የሚባል የፖለቲካ ሰብዕና አልነበራቸውም፡፡ በራሳቸውም አንደበት ተላላኪ ነበርን ብለው ይቅርታ ጠይቀዋል፡፡ የኦነግን ትግል የሚያሳንሱ አሉ፡፡ ነገር ግን ለምን አፈናውን አቁመው ኦነግ በነፃ ምርጫ እንዲሳተፍ አያደርጉንም፡፡ በሕጋዊ መንገድ የሚንቀሳቀሰውን ኦነግ ቢሮውን አፍኖ ማቆየት ለምን አስፈለገ?

ሪፖርተር፡- እናንተ በሰላም ለመንቀሳቀስ ዝግጁ ናችሁ?

አቶ በቴ፡- ለዚያ አይደለም እንዴ ወደ አገር ቤት የገባነው? ስምምነትም የተደረገው?

ሪፖርተር፡- ከገባችሁ በኋላ የነበረው ሁኔታ በተለይ ከትጥቅ መፍታት፣ እንዲሁም በሰላም ከመንቀሳቀስ ጋር በተገናኘ ያራመዳችሁት አቋም የምትሉትን የሚደግፍ ነበር ወይ?

አቶ በቴ፡- የኢትዮጵያ ሚዲያ አንድ ወገን ስለሚከተል እንጂ፣ እኛ ወደ አገር ቤት ከገባን በኋላ ስምምነታችንን ያከበረ አቋም ነው ያራመድነው፡፡ ይህን ደግሞ በተደጋጋሚ ገልጸናል፡፡ የኦነግ ሠራዊት ትጥቅ ይፈታል፡፡ ኦነግ ከሽብር መዝገብ ተፍቆ በሰላም ይንቀሳቀሳል፡፡ በይቅርታ አዋጅ መሠረት ከዚያ ቀደም ለተፈጸሙ ወንጀሎች ማንም የኦነግ አባልና አመራር በወንጀል አይጠየቅም፡፡ ጦሩ ደግሞ ትጥቅ ፈትቶ ወደ ካምፕ ገብቶ ተሃድሶ ተሰጥቶት ወደ ፀጥታ መዋቅር ወይም ወደ ሌሎች ሥራዎች እንዲሰማራ ዕድል ይመቻችለታል፡፡ የተወሰዱ የኦነግ ድርጅቶች ኦራ የሚባል ኢንዶውመንት ድርጅትን ጨምሮ የተዘረፉ ብዙ ንብረቶቹ ይመለሱለታል፡፡ በጦርነቱ የት እንደደረሱ ያልታወቁ አባሎች በጋራ ኮሚቴ ማፈላለግ ይደረጋል የሚሉ ነበሩ ስምምነቶቹ፡፡ ከተገባ በኋላ ግን ስምምነቱን በአግባቡ ተፈጻሚ ሳያደርጉ ቆዩ፡፡ በዚህ የተነሳ ነው አሁን ጫካ ያሉት ኃይሎች ወደ እዚህ ሁኔታ የገቡት፡፡ መጀመሪያ ኦነግ ቅቡልነት የለውም ብለው አስበው ነበር፡፡ አገር ቤት ሲገባ ግን የገጠመው የሕዝብ ድጋፍ አስፈራቸው፡፡ ለዚህ ነው ጫና የሚያደርጉብን፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ፓርቲያችሁ በምን ሁኔታ ላይ ነው የሚገኘው?

አቶ በቴ፡- ቢሯችን ታሽጎ ነው ያለው፡፡ አመራሮቻችን ታስረው ነው የሚገኙት፡፡ በምርጫ ቦርድ ሕጋዊ ብንሆንም በብልፅግና ግን ሕገወጥ ተብለን ነው የምንገኘው፡፡ መንግሥት ደቡብ አፍሪካ ድረስ ከታጠቀ ኃይል ጋር የሰላም ስምምነት ለመፈራረም ሲሄድ ዓይተናል፡፡ በሕጋዊና በሰላማዊ መንገድ በምንቀሳቀሰው በእኛ ላይ ለምን ይህን ሁሉ አፈና ያደርስብናል? ከታጠቁ ኃይሎች ጋር የጀመሩትን ሰላም ማስፈን ጥረት ገፍተው ከቀሩት የታጠቁ ኃይሎች ጋር በሰላም ለመፍታት መጣር አለባቸው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- በኦሮሚያ ክልል ንፁኃን በተደጋጋሚ ይገደላሉ፡፡ በንፁኃን ግድያ፣ በደሃ ገበሬዎችና ከፖለቲካ ጋር ምንም ግንኙነት በሌላቸው ዜጎች እልቂት የሚመለስ የኦሮሞ የፖለቲካ ጥያቄ አለ ወይ? እናንተ ለምን ይህን ዓይነት ዘር ተኮር ገጽታ ያለው ጭፍጨፋ አታወግዙም?

አቶ በቴ፡- የምናወግዘው ሁለቱንም ነው፡፡ መንግሥትንም ሆነ ሌላውን እናወግዛለን፡፡ በሰላማዊ ዜጎች ላይ የሚደርስ ጭፍጨፋን በማንም ይፈጸም እናወግዛለን፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ከሽግግሩ ጊዜ ጀምሮ በሐረርጌና በሌሎች አካባቢዎች ጭፍጨፋው ነበረ፡፡ ሆኖም ተጠያቂነት አይታይም፡፡ በበደኖና በሌሎች ቦታዎች ጥቃት ነበር፡፡ አሁን ደግሞ በወለጋ በስፋት እየታየ ነው፡፡

አቶ በቴ፡- ኦነግ በታሪኩ ሕዝብን የጥቃት ዒላማው አድርጎ አያውቅም፡፡ ማንንም ብሔር የጥቃት ዒላማ የማያደርግ ድርጅት ነው፡፡ ኦነግ ሥርዓትን ነው ሲታገል የኖረው፡፡ የኦሮሞ ጉዳትና ጭፍጨፋ ስለማይነገር እንጂ በሌሎች ማኅበረሰቦች ላይ ከደረሰው በላይ ነው እየደረሰበት ያለው፡፡ የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ከሌላው ሕዝብ ጋር አብሮ የኖረ ነው፡፡ ይህን ማኅበረሰብ ከሌላው ሕዝብ ጋር ለማጋጨት የሚደረግ ጥረት ካልሆነ በስተቀር፣ የኦሮሞ ሕዝብ ሆደ ሰፊና ሁሉንም ተቀባይ ሕዝብ ነው፡፡ እልም ያለ አንፊሎ፣ በደሌና ኢሉአባቦር ጫካ ውስጥ አማራና ኦሮሞ አብረው ይኖራሉ፡፡ አብረው ያርሳሉ፣ አብረው ያመልካሉ፣ አብረው ቡና ይጠጣሉ፡፡ እንዲህ የተጣበቀውን ማኅበረሰብ ለምንድነው የምናባላው? እኛ ሥርዓት እንጂ ብሔረሰብ አይደለም የምንቃወመው፡፡ በኦሮሚያ ውስጥ ያሉ ከኦሮሞ ውጪ ያሉ ብሔረሰቦች የእኛው ዜጎች ናቸው፡፡ ኦነግ የበሰለ ፖለቲካ የሚያራምድ ድርጅት ነው፡፡ ኦሮሞ በተፈጥሮው ዘር ሳይቆጥር ሰዎችን አቅፎ የሚቀበል ሕዝብ ነው፡፡ በገዳ፣ በሞጋሳና በጉዲፈቻ ከኦሮሞ ሳይወለዱም ኦሮሞ ይኮናል፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ነፍጠኛ፣ መጤ፣ ሰፋሪና ሌሎች ፍረጃዎች ሌላውን ወገን አያስበረግጉም ወይ? አብሮ ለመኖርና ሌላውን ዋስትና እንዲሰማው የሚያስችሉ ናቸው ወይ?

አቶ በቴ፡- ኦነግ ሕዝብ ላይ ያተኮረ ትግል አድርጎ አያውቅም፡፡ አንዳንድ አዳዲስ ብሔርተኞች ኦሮሞን በመጥፎ ለመሳል የሚያቀርቡ አሉ፡፡ ኦነግ ከሚያራምደው የተሻሉ ብሔርተኛ አድርገው ራሳቸውን የከረረ ብሔርተኛ ሲያደርጉ ይታያሉ፡፡ አንዳንዶች ከኦነግ የተሻሉ ድርጅት መሆናቸውን ለማሳየት አንዳንዴ የኦነግን ቁንጽል ነገር ወስደው የከረረ ብሔርተኝነት ያራምዳሉ፡፡ ነገር ግን የእኛ ብሔርተኝነት የበሰለና ዴሞክራሲያዊ ነው፡፡ ሌላውን ማጥቃትን እንቃወማለን፡፡ ከኢሕአዴግ ዘመን ጀምሮ በኢትዮጵያ የተፈጠሩ ብሔር ተኮር ጥቃቶች ግን አብዛኞቹ በመንግሥት የፖለቲካ ሴራ የተቀነባበሩ ናቸው፡፡ እኛ ይህን እንቃወማለን፡፡ የሐረርጌውና አርባ ጉጉው እኮ በገለልተኛ መርማሪ እንዲጣራ እንፈልጋለን ብለን ነበር፡፡ አሁንም ቢሆን ይህንን እያልን ነው፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- የሰሜኑን ግጭት በሰላም ለመፍታት ተችሏል፡፡ በኦሮሚያ ክልል ያለውን ቀውስ ለመፍታት ምን ቢደረግ ይሻላል?

አቶ በቴ፡- በዚህ ላይ የእኛ አቋም ግልጽና ወጥ ነው፡፡ በአጠቃላይ ከአስመራ ስንገባም የኦሮሞ ሕዝብን ጥያቄ በሰላምና በሕገ መንግሥታዊ ሥርዓቱ መፍታት ይቻላል ብለን ነው የመጣነው፡፡ ሰላማዊ የትግል ሥልት የመረጥነው ለዚህ ነው፡፡ የሰሜኑ ጦርነት ከመጀመሩ በፊት የፖለቲካ ግጭቱና ልዩነቱ በሰላም መፈታት ይችላል ብለን ልዩነቶች በውይይት ዕልባት እንዲያገኙ ስንጠይቅ ነበር፡፡ መወነጃጀሉ ቆሞ ወደ ውይይት እንዲመጣ ስንጠይቅ ቆይተናል፡፡ የሰሜን ዕዝ ስለተመታ ነው ጦርነቱ የተጀመረው ይባላል፡፡ ብዙ መወነጃጀሎች ይሰማሉ፡፡ ነገር ግን ከጦርነቱ በፊት ያየናቸው በሙሉ ግጭቱን አይቀሬ የሚያደርጉ ለጦርነት የሚገፋፉ ነገሮች ነበሩ ከሁለቱም ወገኖች፡፡ በሁሉም በኩል ለጦርነት የመዘጋጀት እንቅስቃሴ ነበር፡፡ ሕወሓት ከመቀደም ልቅደም ብሎ የሰሜን ዕዝን ማጥቃቱ ብዙም ተወቃሽ አያደርገውም፡፡ ከተገባም በኋላ ጦርነቱ መፍትሔ እንደማይሆንና ቆሞ ችግሩ በሰላም ዕልባት እንዲያገኝ ስንጠይቅ ነበር፡፡ በኦሮሚያም ቢሆን ይህንኑ ነው የምንለው፡፡ በሰሜን ያ ሁሉ ዕልቂት ከተፈጸመ በኋላ በሰላም ነው የተቋጨው፡፡ ስለዚህ በሰሜን ጦርነት መፍትሔ ካልሆነ በኦሮሚያ ውስጥስ እንዴት መፍትሔ ሊሆን ይችላል? በሰሜን ችግሩን ለመፍታት የተኬደበት መንገድ ኦሮሚያ ውስጥስ ለምንድነው የማይተገበረው? መንግሥት ፍርደ ገምድልነቱን ያቁም ነው የምንለው፡፡ መንግሥት በሰሜኑ ከተካሄደው ጦርነት ምንም ማትረፍ እንደማይቻል ዓይቶታል፡፡ በኦሮሚያ ያለውን ዕልቂትም በሰላም የማያቆምበት ሁኔታ አይታየንም፡፡

ሪፖርተር፡- ሽምግልና አልተሞከረውምይ? በባህላዊ ዕርቅ ተብሎ ታዋቂ የኦሮሞ ፖለቲከኞችና አባ ገዳዎች ወደ ወለጋ ሄደው አልነበረም?

አቶ በቴ፡- መንግሥት በሰሜንም ብዙ ርቀት ሄጃለሁ ሲል ነበር፡፡ ሽምግልና የሄዱ ሰዎች ሳይቀር ለጦርነት ሲዘምቱ በታሪክ ታዝበናል፡፡ ወደ ወለጋም የሄዱት እምቢተኝነት መርጧል ብለው ነው የተመለሱት፡፡ ነገር ግን በላከው የሽማግሌ ብዛት የሰላም ፍላጎት አይለካም፡፡ አንዴ አድርጌዋለሁና ከእኔ አልቀረም በሚል ግብዝ ምክንያት የሰላም ጥረትን አትተወውም፡፡ ሰላማዊ መፍትሔን ለማፈላለግ ሁሌም ልትተጋ ይገባል፡፡ ነገር ግን በኦሮሚያ እነ ጃዋር ሄደው የተወሰነ ትጥቅ ማስፈታት ችለው ነበር፡፡ ሆኖም የፀጥታ ሥጋት አለ በሚል ምክንያት ሽማግሌዎቹንም በአንድ ማቆያ አጉረው ነው ያቆዩዋቸው፡፡ የታጠቀውን ኃይል ወደ ካምፕ አስገብቶ ተሃድሶ ሰጥቶ ወደ ሰላማዊ መንገድ የማሰማራት ሥራው በተገባው ቃል መሠረት አልተከናወነም፡፡ ጦላይና ወሊሶ ካምፕ አስገብተህና ተሃድሶ ሰጥተህ ሜዳ ላይ የምትበትን ከሆነ ግን ሌላውስ ምን ዋስትና አለው? መንግሥት ከገባው ቃል መደረግ ያለበትን ጥቂቱን እንኳ ባለማድረጉ ብዙዎች ወደ ጫካ ተመልሰው እንዲገቡና ነገሩ እንዲባባስ ተደርጓል፡፡

ተዛማጅ ፅሁፎች

የአካል ጉዳተኞችን ሕይወት የመቀየር ጉዞ

‹‹የሰላም ስምምነት ተደረገ ማለት በጦርነቱ ወቅት...

‹‹ኅብረተሰቡ አስፈሪ ብሎ የፈረጃቸውን ልጆች በመደገፍ...

‹‹ኢትዮጵያ ግብፅን የምታይበትና ግብፅ ኢትዮጵያን የምታይበት...

Monday, November 21, 2022

The largest war in the world: Hundreds of thousands killed in Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict

The largest war in the world: Hundreds of thousands killed in Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict

An estimated 383,000 to 600,000 civilians died in Tigray between November 2020 and August 2022, according to Professor Jan Nyssen and a team of researchers at Ghent University, in Belgium, who are authorities on Tigray’s geography and agriculture. The estimates represent deaths from atrocities, lack of medicines and health care, and hunger. Estimates for the numbers of combatant deaths on all sides start at 250,000 and range up to 600,000.

Source: USA Today

Note: See original for graphics

Tigray, Eritrea and Ethiopia’s 2-year-long civil war has killed more people than the war in Ukraine, yet nobody’s talking about it.

Kim HjelmgaardStephen J. BeardJennifer BorresenRamon Padilla USA TODAY

Published 10:00 AM GMT Nov. 21, 2022 Updated

No working ambulances for a population of more than 5.5 million. No banking services. Hundreds of thousands killed by fighting and famine. A near-total military siege that has all but cut off essential supplies and forced families to stay in touch by word of mouth or through handwritten letters.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has preoccupied U.S. and international policymakers and military planners since early 2022. There has been intense focus on the humanitarian impact, from displaced people to allegations of war crimes, from energy prices to questions around global security, including whether President Vladimir Putin would dare use nuclear weapons.

But there is another, bigger and deadlier conflict in which over the past two years the abject horrors of war have been all but hidden to the West because of a combination of a border blockade, a communications blackout, complex regional dynamics and few visible sustained signs of meaningful engagement from Western capitals.

This conflict, a civil war, is being fought in Tigray, an ancient kingdom in northern Ethiopia, on the Horn of Africa.

Tigray has been under assault from Ethiopian forces led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Eritrean forces led by President Isaias Afwerki and various militias accused of extrajudicial executions, sexual violence and indiscriminate shelling. There has been widespread destruction of civilian hospitals, schools, residences, factories and businesses. Experts say Eritrea is involved in the conflict partly out of a desire to reassert itself on the regional stage and a result of long-running animosity against Tigrayans. The Ethiopian government and Tigrayan forces recently signed an agreement laying out a roadmap for a peace deal, but experts are unsure to what extent it is meaningfully being observed.

How many lives have been lost in Tigray?

An estimated 383,000 to 600,000 civilians died in Tigray between November 2020 and August 2022, according to Professor Jan Nyssen and a team of researchers at Ghent University, in Belgium, who are authorities on Tigray’s geography and agriculture. The estimates represent deaths from atrocities, lack of medicines and health care, and hunger. Estimates for the numbers of combatant deaths on all sides start at 250,000 and range up to 600,000.

Many are dying from starvation and famine.

The U.S. State Department estimated in September 2021 that more than 5 million people required humanitarian assistance and at least 1 million were living in famine-like conditions. According to Tim Vanden Bempt, a researcher affiliated with Ghent University, humanitarian food aid has not covered those needs. A U.N. World Food Program survey in June noted that 65% of the population had not received food aid for over a year.

Tigray’s population has been facing a famine because of the conflict. Because of the blockade and for security reasons, food supplies have not been able to reach millions. Since the signing of the peace accord, the U.N.’s World Food Program has said its trucks are now starting to deliver aid to Tigray. But it’s not clear at what pace or whether acute shortages of essential supplies are reaching those most in need.

Norwegian Kjetil Tronvoll, an expert on Ethiopia who has studied the wider region for decades, says that in many respects the conflict is a “perennial” one in Ethiopian history. “How strong should the center be?” he said, referring to the Tigrayan decision to revolt after Ahmed sought to centralize Ethiopian government power at the expense of regions like Tigray. A joint investigation by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and the U.N. Human Rights Office has concluded that militias loyal to Tigray have also likely committed war crimes during the conflict.

Tronvoll said the November signing of the peace accord between Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which controls much of Tigray, was a “significant and great step forward toward a durable peace. But we are not there yet. This is just the beginning.”

Hospitals and medical services are in disarray.

“We can’t even communicate with our families because no cellphone services or landlines are functioning,” Abenezer Etsedingl, a Tigrayan doctor who coordinates emergency medical services for the region’s 40 hospitals, told USA TODAY in early November. He said that at least 12 of the hospitals have fallen to Ethiopian and Eritrean armed forces over the past two years.

Etsedingl is not able to communicate with staff at any of the hospitals without actually going to visit them. Before the war broke out, Tigray had about 270 ambulances. Now there are just eight. With no available fuel, none are on the road. Etsedingl said many patients are taken to hospitals by horse-drawn carts. Once there, if they do get a diagnosis, there are no medicines to treat them. Maternal mortality rates have have shot up 800%, he said.

Etsedingl spoke to USA TODAY via WhatsApp, the messaging platform. As a government employee, he had rare access to a satellite phone that gave a patchy connection to the internet. His is the only Tigray hospital, in the city of Mekelle, that has one. It was not possible to independently verify Etsedingl’s claims.

Who’s fighting who in Tigray?

The Ethiopian government, led by Ahmed, is supported by Eritrea’s leader, Afwerki, and his army. They have been fighting the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Tigray’s ruling party. Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) has 300,000 troops, according to Tronvoll. Eritrea’s military is called the Eritrean Defense Forces, or EDF. Tronvoll says it has 250,000 troops. Another militia, the Amhara regional forces, are also fighting against the Tigrayan Defense Forces.

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) led by Debretsion Gebremichael and its army of 250,000 troops is supported by several other militias, the largest of which is called the Oromo Liberation Army, or OLA, led by Kumsa Diriba (aka Jaal Marroo), which has 150,000 troops. Another militia called Somali State Resistance supports Tigray.

Tronvoll says the above are estimates and could fluctuate by 50,000 in either direction. He says they represent the total number of fighting forces rotated in and out of the conflict.

How many people live in Ethiopia, Eritrea and Tigray?

The Tigray region’s population comprises 4.9% of Ethiopia’s 117 million people. Ethiopia is the oldest state in sub-Saharan Africa and the only state in Africa that has never been colonized. It has more than 2,000 years of history. It is where the oldest biblical texts have been found. Various forms of Pentecostal Christianity are widely followed in Ethiopia, including by Ahmed, who uses religious terminology in his speeches to explain his own power. He claims he has a divine mandate.

Ethiopia is an “extremely religious society,” says Tronvoll. He says this devotion is equally shared among the nation’s Muslims, Orthodox Christians and Pentecostal Christians.

Ethnic Tigrayans are chiefly Orthodox Christians adherents (Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo). They are mainly farmers and the largest industry is agriculture. The main language in Ethiopia is Amharic. In the Tigray region, Tigrinya is spoken. These two languages are closely related. Both are known as Semitic languages. Tigrinya is not too different from what’s spoken in Eritrea.

Who was involved in the latest peace deal?

The warring factions in Ethiopia signed a peace deal aimed at drawing down the fighting and restoring services and aid to Tigray. Here are the key figures in the negotiations:

The African Union, made up of 55 states, is mediating the peace talks. Former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo is acting envoy for the talks. Getachew Reda is the representative for Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), and Redwan Rameto is representing the Ethiopian government. The Biden administration’s special envoy for the Horn of Africa, Mike Hammer, is also involved.

With virtually every part of Tigray cut off from every other, Etsedingl, the Tigrayan doctor, said he didn’t know if the agreement to end hostilities, described by Ahmed as “monumental,” would mean a breakthrough on the ground.

Published 10:00 AM GMT Nov. 21, 2022 Updated

Friday, November 18, 2022

US Sanctions against Eritrea and arms for Tigray

US Sanctions against Eritrea and arms for Tigray

Two interesting pieces of information.

US Sanctions

The first was the assurance that US Congressman Brad Sherman was given on Thursday 17th November by the US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Molly Phee, that Washington would impose further sanctions against Eritrea, if its troops did not withdraw from Ethiopia.

In this exchange, Congressman Sherman accuses Eritrean troops of committing atrocities inside Tigray, saying “there is no legitimate reason for Eritrea to be inside Ethiopia.” He then asks: “Will you support additional sanctions on Eritrea, if they fail to withdraw their troops, including sanctions on President Afewerki himself, and on mining in Eritrea?”

Phee replies that she “absolutely” concurs with the Congressman’s negative assessment of Eritrea’s role in Ethiopia and that it is “positive” that the role of foreign forces is part of the Pretoria and Nairobi agreements. The Congressman then says: “But if Eritrea does not withdraw, you would do those sanctions? To which Ms Phee says, yes.

Congressman Bradshaw also asks about not restoring Ethiopia’s access to American markets via AGOA (a development which cost Ethiopia thousands of jobs in the clothing sector) and that the US would not support financial aid to Ethiopia via the IMF or World Bank, until full restoration of aid and services, including the internet, to Tigray. Ms Phee says Washington has “made clear to the Ethiopian government that full implementation of the Pretoria and Nairobi agreements is essential to restoring the partnership which we enjoyed.”

She also said that the freeing of tens of thousands of Tigrayans from detention centres was part of the US’s dialogue with “all those who committed atrocities during this terrible conflict.”

Arms for Tigray

Abren, which describes its website as written by “a group of Ethiopian Americans in the Washington D.C., Maryland, and Virginia area who envision a strong and mutually beneficial relationship between the United States and Ethiopia” published an interesting article on 29 August, which is reproduced below. I missed it when it was first published.

For context, there were other reports at the time of flights into Tigray, but it was never clear exactly what they carried and what happened to them. This is confirmed by other journalists. Abren asked an interesting questions:

“did Ethiopian authorities sit on this intelligence, and if so why? A few days ago, the Ethiopian air-force reported the downing of an Antonov 26 flight in Ethiopian airspace. How long had this been going undeterred or undetected? Five months since April?”

The flight analyst, Gerjon, published a separate analysis of the story, which is also reproduced below.

This is his conclusion.

The question that arises in all of this is: does this prove that the shootdown actually happened? Given the level of detail and the realism of the route information in the Ethiopian Air Force whiteboard map, it does not seem unlikely that something did indeed happen here. In other words: if it’s a fake, it’s a very good fake. It now seems more likely that these flights from Sudan into Tigray do indeed exist.

However, a lot of information is still missing: Who is the operator of the aircraft? What is the registration of the aircraft? What route is it operating on? What sort of cargo was it carrying? More importantly, there is no evidence for an actual shootdown. There is no video proving a shootdown, there are are no pictures of a wreckage and no known sightings of a recent wreckage on satellite imagery either. Because these questions are still unanswered, I remain undecided about what really happened here.

Many questions still outstanding…

Secret Foreign Flights Arming TPLF

AUGUST 29, 2022

In an April 2022 podcast, William Davidson of the Crisis group indicated he had “Solid Evidence” of TPLF re-arming itself, thanks to dozens of Antonov flights from Sudan to the Tigray region of Ethiopia. His claim that evening flights had been taking place was hardly noticed, but there is also some evidence of locals noticing these flights. However, the wider Ethiopian public had little knowledge of this fact.

William Davidson of the International Crisis Group hinted there have been arms laden cargo planes delivering weapons to the TPLF for some period of time From April 2022 until August 2022.

On August 24, 2022, Prime Minister of Ethiopia revealed they had knowledge of arms laden foreign cargo flights flying in at night from Sudan into Shire airport in the northern Tigray region. According to the prime minister, Ethiopian intel had known of these overnight flights for several months and had tangible information about their origin and their payload.

This revelation is indeed monumental. It discloses several things. For one, it shows the extent to which the TPLF has become a proxy for regional actors seeking to destabilize Ethiopia. Second, it shows the extent to which foreign patrons of the TPLF are willing to go to sustain the insurgency. Thirdly, now that the issue has been made public, it inevitably becomes an inflection point likely to drag more outsiders into Ethiopia’s northern conflict. Lastly, it behooves the Ethiopian authorities to demonstrate clearly how this has been happening and for how long.

Ethiopia’s Air Force Chief in press briefing revealed the shooting down of arms laden cargo plane headed for TPLF rebels in Tigray for the first time on on August 26, 2022.

Indeed, there are so many unanswered questions here, but overall, the revelation only adds a level of credence to what many had already suspected. TPLF’s overt invitation for Egyptian support was perhaps missed by many Western observers since the discourse had been largely in Tigrigna and among supporters. Nonetheless, the desire to do so has always been there, and now has come to full fruition.

The flight paths are also another point worth considering. Flying right below the town of Humera and coming from the direction of Sudan is clear collusion by Sudanese authorities. Even if flights are not originating from Sudanese bases, certainly the government in Khartoum is aware and gave greenlight for its air space to be used by a third party.

Lastly, did Ethiopian authorities sit on this intelligence, and if so why? A few days ago, the Ethiopian air-force reported the downing of an Antonov 26 flight in Ethiopian airspace. How long had this been going undeterred or undetected? Five months since April? Public interest to all of these questions will likely prompt parliament to demand the details. The Ethiopian public should know the dangerous role of foreign actors in perpetuating the conflict in the north.

Shot down or not shot down? Assessing Ethiopian Air Force claims.

Aug 27

On Wednesday 24 Aug 2022, Ethiopian leaders first claimed the shootdown of an Antonov An-26 transport aircraft that had entered restricted airspace over Northern Ethiopia. However, concrete evidence for the event has yet to be presented. This might be because much of the war-torn Tigray region remains cut off from the rest of the world, because of long-term internet shutdowns going all the way back to late 2020. On 26 Aug 2022, Ethiopian Air Force Lt. Gen Yilma Merdassa appeared in a video published by the FanaBC channel, providing more details about the incident. In this blog post, I will analyze the data published in this video, and assess its authenticity.

The story

Because I do not speak Amharic, I was unable to understand the words of chief commander of the Ethiopian Air Force, Lt. Gen. Yilma Merdassa, interviewed in the video. However, I spoke to three different local people of different ethnical backgrounds, and asked them to translate his statements. According to them, Lt. Gen. Merdassa’s overview of the situation can roughly be summarized as follows:

“Civil and military radars tracked an Antonov An-26 entering Ethiopian Airspace from Sudan on 24 Aug 2022, entering a no-fly zone and not following approved routes. In Northwestern Ethiopia, overflight above 29,000 ft [Lt. Gen. Merdassa likely meant ‘below’ here, matching NOTAMs] is prohibited because of the conflict. The aircraft and its destination were unknown to Ethiopian authorities, prompting the Ethiopian Air Force to scramble a Sukhoi Su-27 to investigate. The crew of the Antonov An-26 was asked to turn around, but did not comply. Finally, the An-26 was shot down around 21:30 local time.”

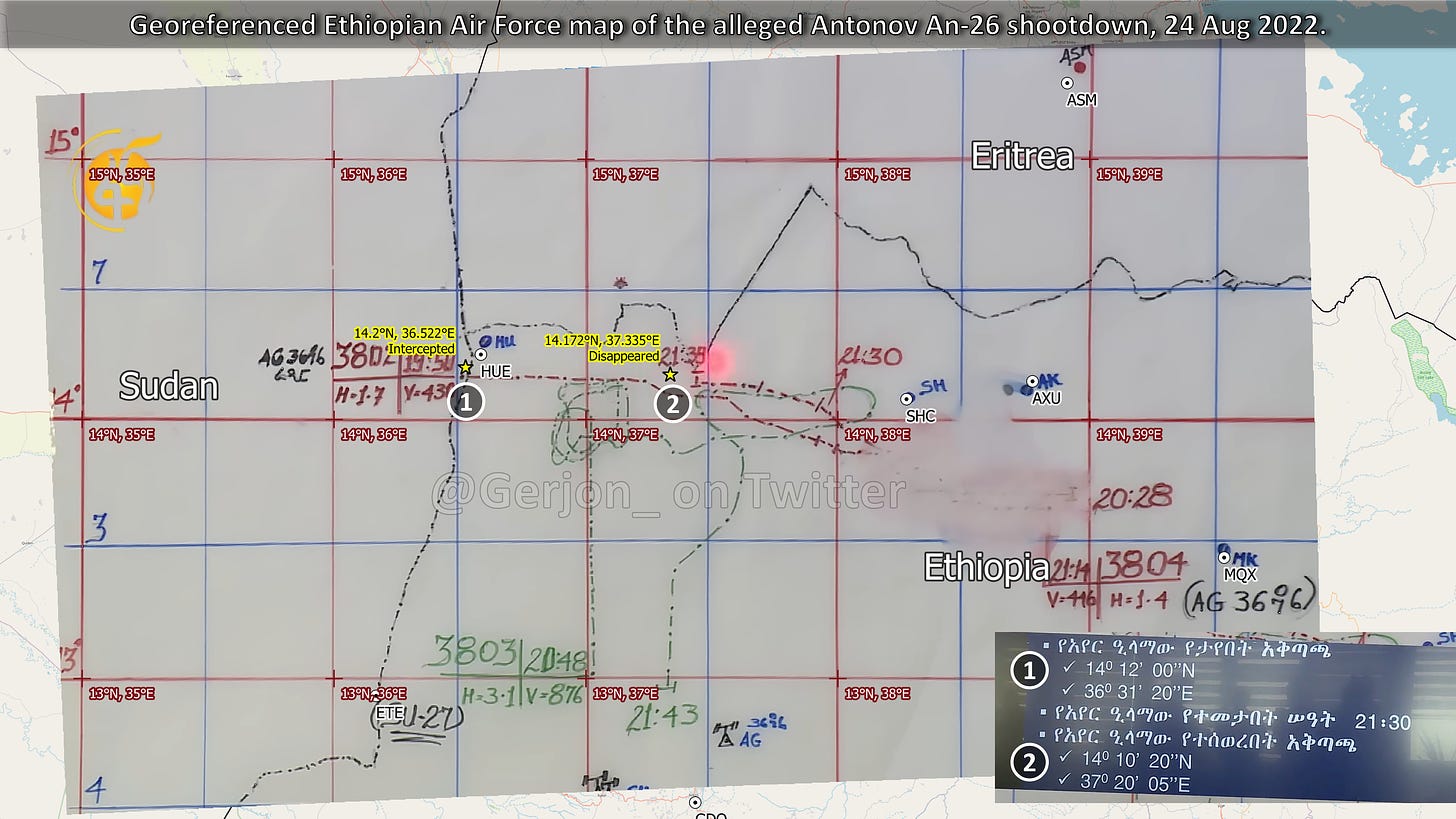

One of the key sources of information presented in the video, is an apparently hand-made whiteboard map of the situation. This map reveals several details not mentioned by Lt. Gen. Merdassa.

The map

My first challenge analyzing this map was adding a georeference, to allow me to do measurements based on this map. The horizontal and vertical red lines across the map represent degrees of latitude and longitude in the WGS 1984 coordinate reference system. Their 15 intersections (labeled in red) allowed me to easily and accurately georeference the map using a second order polynomial transformation.

The dashed black lines in the map represent international borders, with Sudan to the west, Eritrea to the Northeast and Ethiopia to the Southeast. Blue and red dots scattered around the map correspond to cities (or perhaps their nearby airports): HU for Humera (IATA code HUE), SH for Shire (SHC), AK for Axum (AXU), MK for Mekele (MQX), and to the north ASM for Asmara (ASM), the capital of Eritrea. Corresponding white dots are the actual locations of the airports, retrieved from a global airport dataset. The green line shows the route of an alleged Ethiopian Air Force Sukhoi Su-27 air superiority fighter. The red line is the route of the alleged Antonov An-26, a propellor transport aircraft.

Labels with additional information have been added by the Ethiopian Air Force, allowing us to reconstruct a timeline of the events.

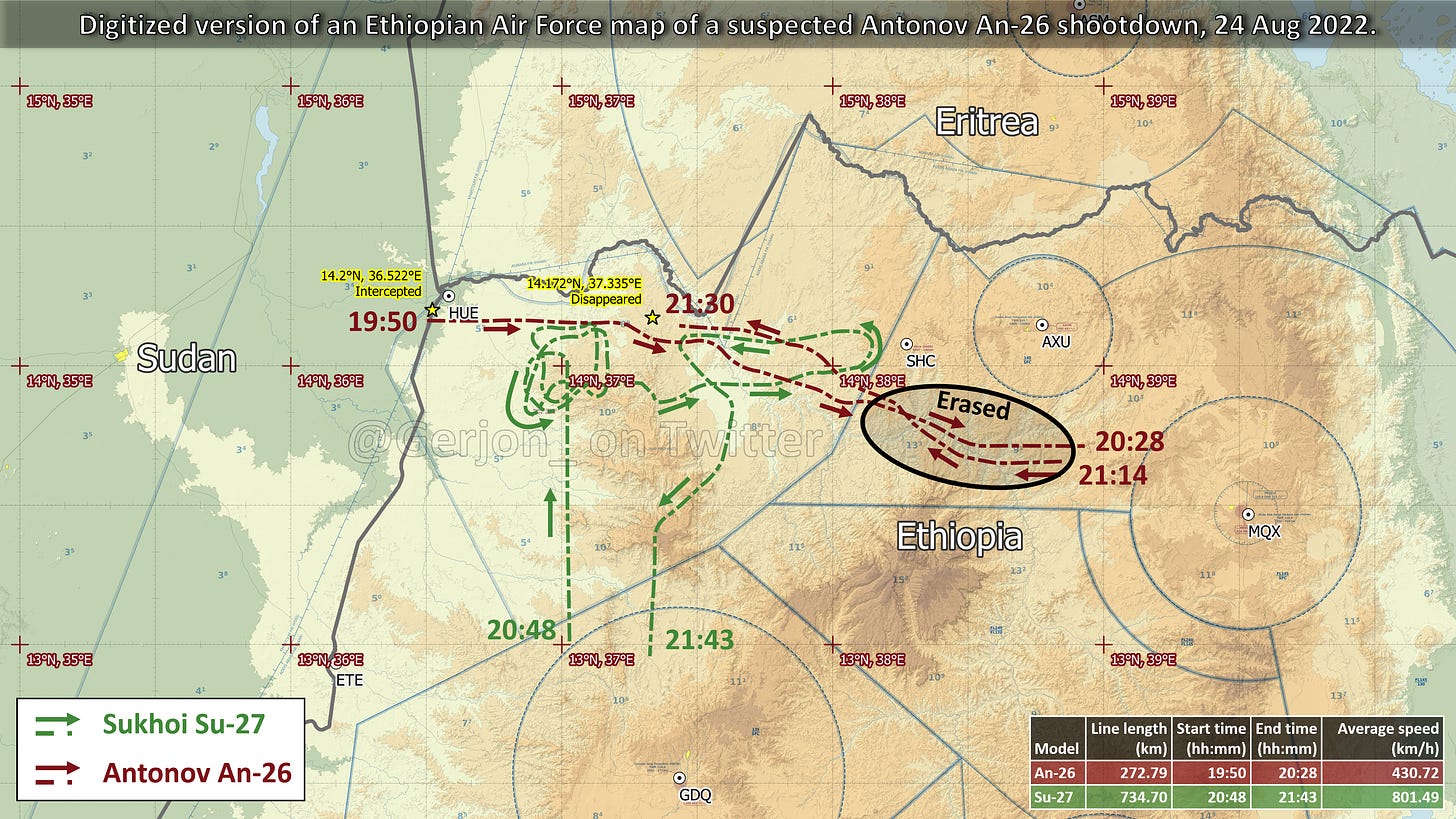

The timeline

According to the labels, the An-26 (red line) first entered Ethiopian airspace around 19:50 local time. This matches the location of “interception” (or entering radar coverage?) shown later in the video, 14° 12’ 00”N, 36° 31’ 20”E, indicated with 1 on the whiteboard map. This location is very close to the border between Sudan and Ethiopia.

Following the line, we can see that the aircraft continued east. South of Shire and Axum, it looks like the line has largely been erased. However, it is still visible that the line ends SSE of Axum at 20:28. Presumably the aircraft then left Ethiopian radar coverage. Looking at the available time and direction of flight, the aircraft might have been descending for Mekele, capital of the Tigray region, located some 70 km further east.

At 20:48, 20 minutes later, an Ethiopian Air Force Sukhoi Su-27 air superiority fighter entered the Tigray region, circling over Northwesternmost Ethiopia, far west from the position of the An-26.

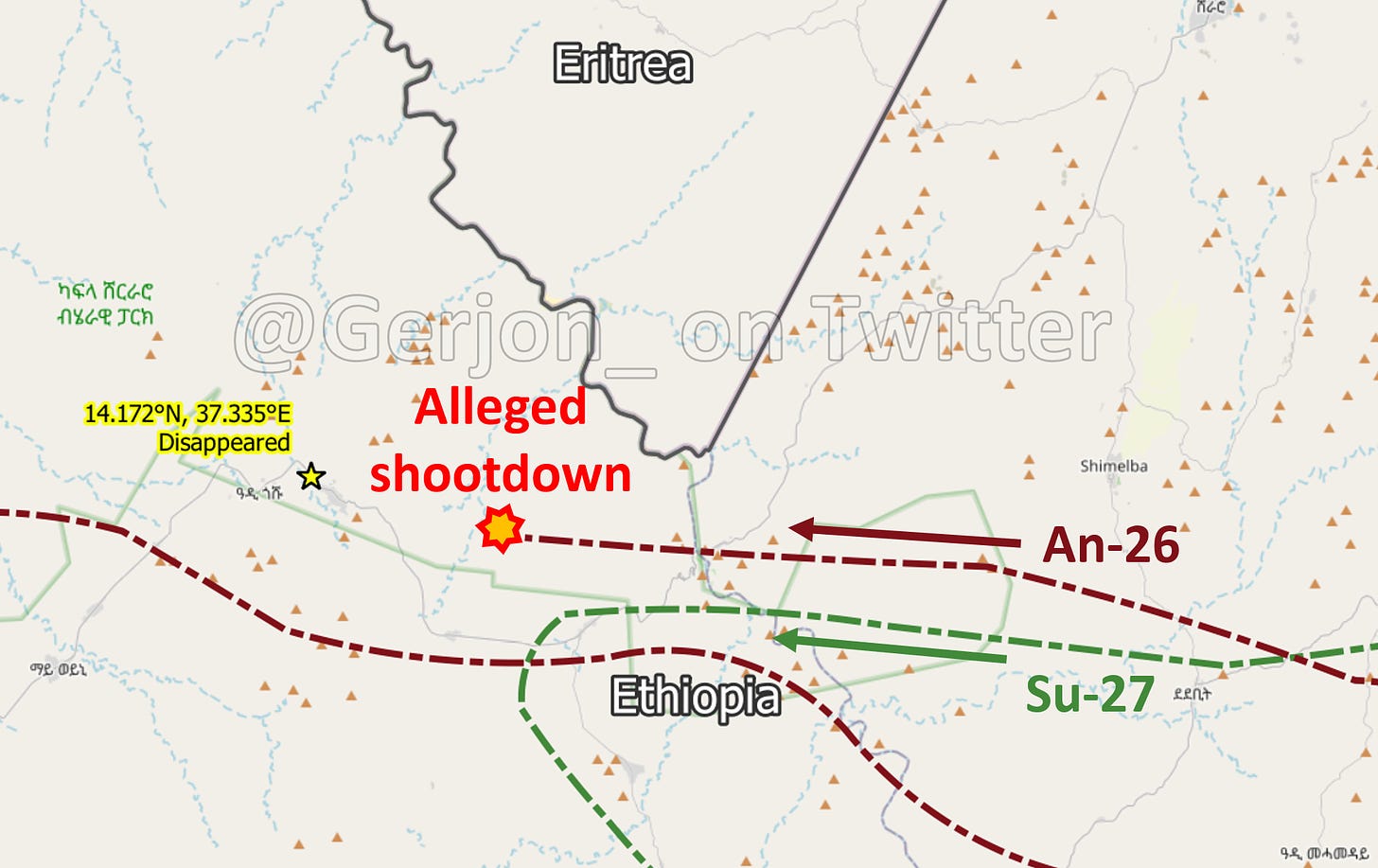

At 21:14, around 45 minutes after “disappearing” near Mekele, the Antonov An-26 popped back up west of Mekele, near where it was last seen, and went on its way back to Sudan. According to the map and Lt. Gen. Merdassa, the aircraft was shot down around 15 minutes later, at 21:30, and was last seen around 14° 10’ 20”N, 37° 20’ 05”E, where it again “disappeared”. This location marks the alleged crash site of the aircraft and is marked with 2 on the map, and is close to the location where the Su-27 turned South, leaving the area.

There are clear differences between the story described on the map and the story described by Lt. Gen. Merdassa. The most significant difference is that the story of the Lt. Gen. Merdassa does not mention what happened between 20:28 and 21:14, and does not describe that the aircraft ever left Ethiopian radar coverage and may have even landed in Mekele.

One of the steps in my analysis was to check whether the routes drawn by the Ethiopian Air Force could be realistic. I therefore calculated the average speed of the flight into Ethiopia by the An-26 and the Su-27. My measurements of the route length of the flight portions drawn by the Ethiopian Air Force equal 272.79 and 734.70 km for the An-26 (heading east) and Su-27 respectively.

According to the labels added to the map, the An-26 and Su-27 entered the region flying at a velocity (v) of 430 and 876, respectively. Although no units are given, the only realistic unit here is km/h. Combining the route length mentioned above with the timestamps given on the map, the An-26 and Su-27 had an average speed of 430.72 km/h and 801.49 km/h respectively. These values are very similar to the values indicated by the Ethiopian Air Force and seem realistic for the respective aircraft types.

At 876 km/h, the initial speed of the Su-27 was slighly higher than my calculated average speed. This can be explained by the fact that the Su-27 intercepted the An-26, and may have slowed down to keep up with the it, before it got shot down. This is confirmed by the map, which shows a parallel green and red line near the location where the An-26 got shot down at 21:30, as shown below. Following the shootdown, the Su-27 turned south, likely returning to base.

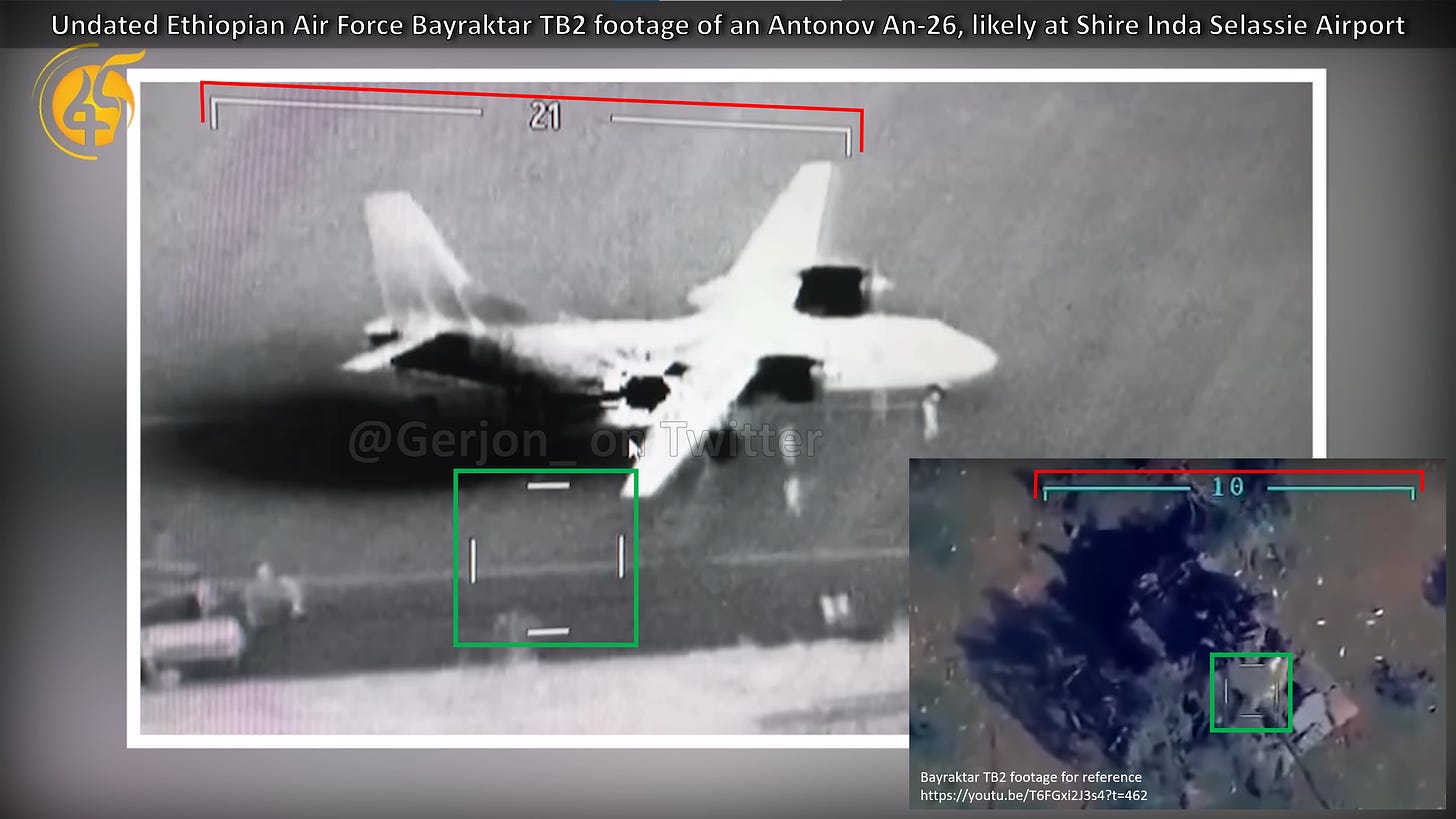

Footage from a Bayraktar TB2

At 01:53 in the video, an image of a propellor aircraft (likely Antonov An-26) can be seen. Judging by the level of detail and angle, the footage was likely made from a UAV. The Ethiopian Air Force is known to operate three types of UAVs: Iran’s Mohajer-6, China’s Wing Loong and Turkey’s Bayraktar TB2. Comparison of online footage of the interfaces of each of these drones to the footage seen in the video leads me to conclude that this footage was likely made by a Bayraktar TB2 UAV.

In the example below, I found similar footage made by a Ukrainian TB2 . Both clips feature a central scale bar to the top (red) and a ‘crosshair’ consisting of four lines in a square shape (green).

The next question that arises from this clip, is where it was made. Upon close inspection, we can see that the An-26 is parked on top of a line. Below and in parallel with the wings of the An-26, a second line can be seen, which becomes wider towards the end (yellow U-shape in the image below). Perpendicular to this wider portion is a second line (blue), followed by what looks like a road with vehicles and people. This road marks the edge of the apron. Next to the road, vegetation can be seen. No taxiways or other features can be seen.

I have been able to identify two airports in Ethiopia that exactly match this description: Robe Airport in Oromia and Shire Inda Selassie Airport in Tigray. Given the ongoing conflict, I consider it more likely that the video was made at Shire Inda Selassie Airport.

Looking at the route information on the map, it however seems unlikely that Shire was the destination of the 24 Aug 2022 flight. The imagery provided may therefore be archive imagery of an earlier flight. This footage could confirm earlier claims of cargo flights from Sudan landing at Tigray airfields, for which no evidence has been found so far. It is also in line with statements by PM Abiy Ahmed Ali and Lt. Gen. Merdassa that Ethiopia has been monitoring earlier similar flights, without taking direct action against them.

Final assessment

The question that arises in all of this is: does this prove that the shootdown actually happened? Given the level of detail and the realism of the route information in the Ethiopian Air Force whiteboard map, it does not seem unlikely that something did indeed happen here. In other words: if it’s a fake, it’s a very good fake. It now seems more likely that these flights from Sudan into Tigray do indeed exist.

However, a lot of information is still missing: Who is the operator of the aircraft? What is the registration of the aircraft? What route is it operating on? What sort of cargo was it carrying? More importantly, there is no evidence for an actual shootdown. There is no video proving a shootdown, there are are no pictures of a wreckage and no known sightings of a recent wreckage on satellite imagery either. Because these questions are still unanswered, I remain undecided about what really happened here.